WHILE KHAMISI BEGGED IN THE MARKETPLACE, he kept a sharp eye out for certain slouching characters. For years he had watched them in longing. For months he had watched in eagerness, exhilarated to have been taken into the group. But today – today he watched in dread.

He knew they’d be angry at what he had to say, to do. Better to slink out of their path than face that fate.

He didn’t watch closely enough. A hand clapped him on the shoulder from behind, and Jafari’s voice hissed in his ear. “Where’ve you been? You knew what time to meet!”

Khamisi choked back a squawk. “I can’t!” he blurted as the older man dragged him toward a shadowed lane.

“You can, and you will. You know we need two lookouts for this job.”

“But I’ve been warned I shouldn’t—”

“Warned? Who’ve you been talking to?” Jafari’s grasp turned to sharp-edged steel.

“No one! Told no one, not a soul!”

“Then how could you get a warning, if no one knows the plan?”

Khamisi trembled. He bared his teeth in fear until his cheeks hurt.

“Don’t grimace at me, you ugly monkey!” Jafari shook the young man, then shoved him up against the rough, coral-block wall. “Who’ve you talked to? No lies, or I’ll throttle you!”

Khamisi begged with his gaze, not daring to shy away from Jafari’s anger. So much the thieves could read in a look, a glance. “I was w-w-warned in a d-d-dream! Never s-s-spoke to no one live!”

“A dream?” Jafari clenched a hand tight around Khamisi’s scrawny throat. “I should do it. But I’ll leave the pleasure to Mwita.You truly are a witless, ugly, jabbering monkey. Useless!” He threw the young man to the cobblestones.

Khamisi scrabbled back to his feet, coughing and wary.

Jafari goaded him along the lane and through a dark doorway.

Mwita, Jafari, and Zuberi pummeled Khamisi with questions and fists until satisfied he hadn’t betrayed them. “A dream!” spat Mwita, the ringleader.

“M-m-mamba Munti herself,” Khamisi protested. “She told me not to go this time!”

“Go this time, or I myself willl feed you to Mamba out in the bay, let her drag you down to your death.”

Khamisi groveled.

“If you value your miserable life, you’ll do it,” Mwita threatened. “Zuberi will be watching you.” He turned to the others, went over their plan for breaking into the guesthouse. “He’ll have gold and jewels in a locked chest. Jafari, you carry the pry-bar under your robes. Is your brother ready to climb the wall? Good. Here’s the rope to carry up.”

Jafari herded Khamisi to his lookout post across the square from the guesthouse just as its doors opened. Out strode the great man himself, the Muslim scholar Ibn Battuta, beginning his tour of the fabled trading city Kilwa Kisiwani. Like everyone else, Jafari gaped at the sight of brilliant robes and turban and the hawk-nosed, bearded, northern face.

Khamisi glanced around. Zuberi wasn’t in place yet. The young man ducked and ran, hobbling at a crouch. He slunk behind the stalls of oranges and lemons. He skirted tables displaying porcelain from China and spices from the Indies. He ran down an alley away from the Great Mosque with its pillared corridors and vast dome.

Footsteps slapped in pursuit.

Khamisi hid near the Small Domed Mosque before dashing to the closest city gate. The wrong one. This road didn’t lead to the mangrove swamp where he could have found easy hiding. It led out toward the sea-side of the island.

He glanced back. “No, no, no,” he groaned. Jafari was on his trail.

Khamisi scurried best he could with his twisted gait all the way out to Husuni Kubwa, the Queen’s House, where the massive complex perched on a bluff overlooking the eastern sea.

Jafari had halved the distance between them.

Khamisi pattered down the score of steps to the beach, not knowing what drew him, just knowing he needed to reach the water.

Mamba Munti was waiting. Her hair furled about her on the shining waves like trailing lianas in the swamp, long, springy, coal-black tresses. Her dark skin glimmered with scales. Her smile wove peril with beauty. “Come,” she sang, holding out her graceful arms.

Khamisi didn’t pause to wonder why the siren wanted him, the twisted, ugly beggar. He waded into the waves.

Behind him, on the sands, Jafiri gasped in astonishment. “She’ll devour you!” he cried.

Khamisi did not slow, but walked out beyond his depth and let the waters close over him.

Years later, when Khamisi returned to the bustling Swahili city of Kilwa Kisiwana, he walked with grace and strength. His features shone with nobility and comeliness, and his pouch never lacked for gold.

Based on legends of Mamba Munti (East Africa, Swahili) and Mami Wata (West Africa); Tanzania, AD 1331

text: © 2021 Joyce Holt

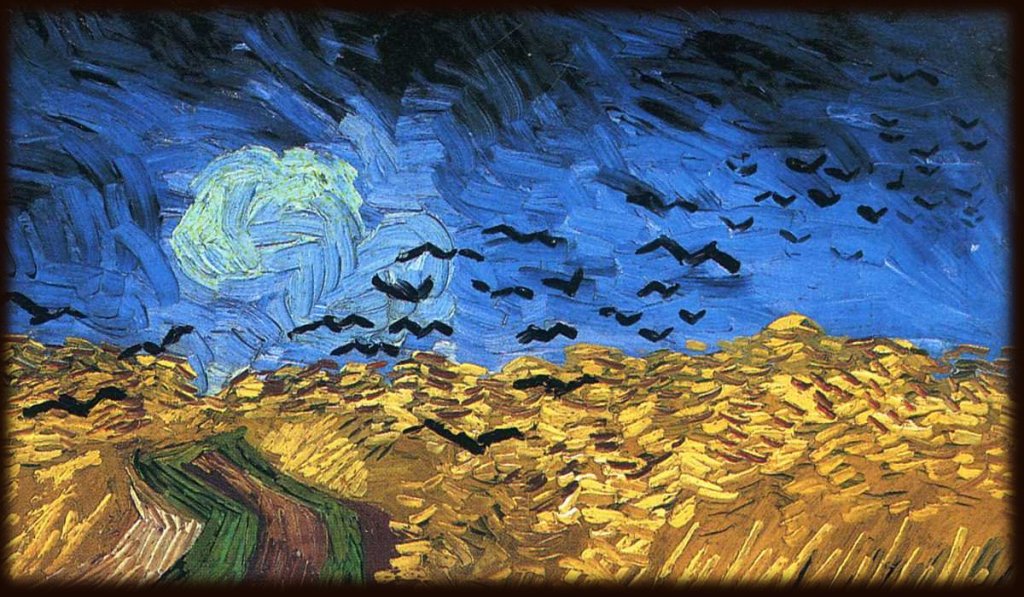

artwork: 16th century painting: in the public domain, according to these sources:

wikiart: “This artwork is in public domain in its country of origin and other countries and areas where the copyright term is the author’s life plus 70 years or less.”

wikipedia: “This work is in the public domain in its country of origin and other countries and areas where the copyright term is the author’s life plus 100 years or fewer.”

{{PD-US-expired}} : published anywhere (or registered with the U.S. Copyright Office) before 1926 and public domain in the U.S.