A SMOLDERING TORCH IN ONE HAND and his lifeline gripped tightly in the other, Ágeirr lowered himself down Gívrinarhol, a shaft that plunged deep into the bluff. The grinding noise in the depths grew louder as he slid and bumped along the rocky walls.

His feet settled to ground again. He let the rope hang slack, held up the torch. Its flicker lit a vast cavern echoing with the sound of stone on stone.

There! A figure moved. He caught his breath.

The tales were true! A giant woman dwelled here, an ogress hunched over a great low slab of a table, cranking away at a mill.

She slowed, lifted her hoary head, glanced around in all directions. Her gaze swept right across Ágeirr without taking note. Her milky-white gaze. Blind. She went back to milling.

Ágeirr tiptoed closer.

The ogress went on with her work.

Ágeirr lifted the torch to see what came out of her mill.

Golden nuggets!

He edged closer, within reach, scooped gold, slid it into his pocket. Another fistful. His hand froze on its way for more.

The ogress had stopped grinding.

Ágeirr could have sworn he’d made no noise, but the giant woman spoke in a voice nearly as rough as her mill. “There’s a mouse or a thief prowling around here, or something is wrong with my old mill.*”

He edged away, then in a panic broke into a run. At the shaft he dropped the torch and grabbed the rope, hauling himself up hand over hand.

Behind him heavy feet slapped and clawed hands scraped stone. The ogress bellowed, “Thief! I’ll have you! Sand and stone, where has he gone? Halla, Halla, neighbor mine! Help me in the hunt! A thief! A thief! He’s climbing the shaft!”

Two ogresses after him! Ágeirr reached the top of Gívrinarhol. He leaped astride his horse and set off down the bluff. He could see below the shining waters of the lake, and beyond that, in the east, the village of Sandur where safety lay. Not safety in walls or castles or swords or snares, but safety in the church that reared like a spear against the sky. A spear that cast terror into all otherworldly creatures.

Ágeirr reached the foot of the bluff before the neighbor ogress broke into the open at its height. Thundering footfalls, howls and shrieks loud enough to shake leaves from trees, the giantess came hurtling after him.

He had a good headstart, Ágeirr believed. A swift horse. Not far to go once he rounded the lake – and in moments he was halfway around.

He glanced over his shoulder – and nearly fell from his horse. The ogress wasn’t swerving. She was heading straight at the lake and gathering herself for a leap.

Ágeirr whipped up his horse, kicking madly. The wind swung about, bearing the monster’s scent. The mare lit into a pelting run.

The ogress landed from her lake-spanning leap. The island shook. Boulders crashed.

A horrendous snarling came closer and closer. The poor horse shrieked, and Ágeirr felt a jolt. The ogress had caught the mare by the tail!

Panicked, the horse lunged ahead with all its strength.

Snap!

The mare squealed as she leaped back into a gallop, leaving her plumed tail in the monster’s grip.

Over the last ridge they pelted. There ahead rose the spire of Sandur’s church.

The ogress gave one last howl, then turned and trudged back toward the bluff, the cavern, and Gívrinarhol.

Her footprints can still be seen both sides of the lake, and still, at the mouth of Gívrinarhol, you can hear the grinding of gold far down in its depths.

* line taken straight from the folktale, from Sandøy, Faeroe Islands

text: © 2022 Joyce Holt

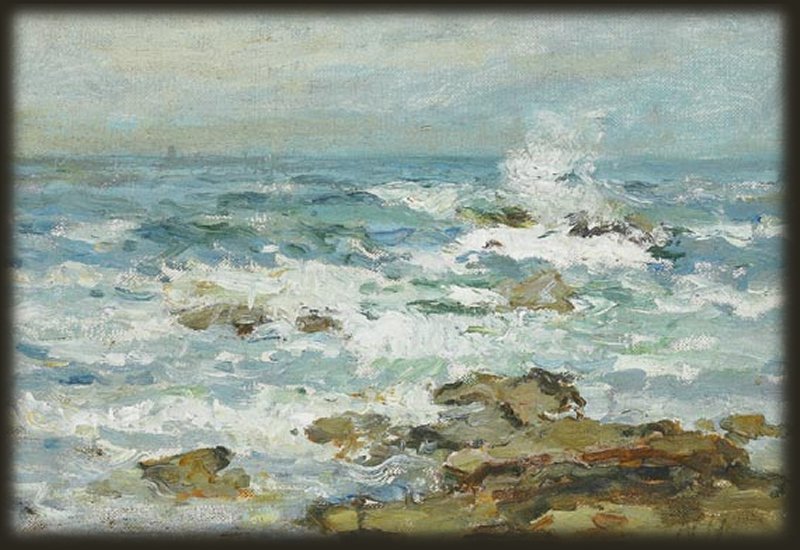

artwork: 19th and early 20th century paintings. Public domain info here.