THE GRANARY RAFTERS RANG with fiddle music, stomping feet, and laughter till long past midnight. Country folk knew how to have a grand time even in the midst of the Great Depression.

Groans arose when the fiddler announced he only had one more song in him. Jesse’s latest dance partner fluttered fingers goodbye and sashayed off with a cluster of gals toward the Saddler granary doors.

A girl in blue gingham caught his eye. “I’m not leaving yet,” she said. “Ask me for the last dance!”

Jesse grinned and whirled her through the last square dance. Sally, it turned out, hailed from up Cloverdale way, and would be staying the weekend here with her cousin, Alice Saddler.

“How far do you have to go tonight?” Sally asked.

“Not far. I’ll bunk with my pals in Grantsburg,” Jesse said. He jabbed a thumb at one of his buddies. “I brought him and his brothers.”

“Grantsburg? Isn’t that a long way round?”

“Nah. Cross the river, up the bluff, then twelve miles or so due south.”

“Across the river?” She screwed up her face in question. “The Saint Croix? There’s no bridge for miles!”

“Don’t let a balmy March thaw fool you,” Jesse said. “The ice is still two feet thick. That’s how we came tonight. My Model T handled it just fine.” The four inches of standing water atop the ice hadn’t slowed them at all.

Another of Jesse’s pals came in from seeing his gal off. “Temperature’s dropped,” he said, stamping to warm up again. “Brrr! New crust of ice everywhere.”

The dance ended. Jesse gave Sally a bow of farewell then joined his buddies and headed for his car. As he stepped out of doors, a savage wind attacked out of the northwest, gnawing at every inch of bare skin. Frigid slush soaked his ankles. His heart chilled as well, thinking of his rubber galoshes foolishly left at home.

Never mind. Engine heat wafting up through the floorboards would soon put that to rights.

Jesse cranked the Model T’s engine while his buddies piled in, laughing and joking, full of high spirits. The car rumbled to life, and in moments they trundled out of the farmyard and down to the riverbank, wooden wheels crunching through the new crust.

They made it across the river just fine, but the bluff beyond was a different matter. On their way coming, the wheels had sunk through slush and gotten grip on the sand beneath. Now it was all ice. They had no traction. Wheels spun to no avail.

“All right, fellows, out and push!” Jesse ordered.

Straining and slipping, grumbling and groaning, inch by inch, in bitter cold, the four young men fought their way at last to the top of the bluff.

(The boundary between Wisconsin and Minnesota runs along the St Croix River.)

Years later, in 1979, my great-uncle Jesse summed up that night’s adventures:

“All of us felt we were half-frozen to death. We were young and didn’t have much common sense, so we all had put on our suits with low shoes and no rubbers or overcoats. We just had to suffer the cold until we reached home.

“As I think back about traveling in those old time cars, I have to admit we were brave to go places, especially in the winter with such cars that were in such bad shape. If I had one of them today I wouldn’t take a chance on a ten-mile trip with it.

“Little did we know that in a few years cars would be made dependable, with speeds of up to one hundred miles an hour, motors that would often go 200,000 miles, tires 50,000 miles, and highways that you can travel on at 55 miles per hour, and it would seem as though you were sitting still.”

A couple other notes by Jesse about the Model T:

“I never had a broken arm from cranking my car, but a couple of my friends did. When I bought my first car, my oldest brother Raymond warned me not to be directly over the crank, but to reach out to it at a slant, then in the event it backfired, it would not break loose from my hand and strike my arm…”

“In 1934 I bought a 1929 Model A roadster. When I had to go to town for groceries, it was always a job to start this car. I finally learned that if I took a kettle of boiling water and poured it slowly on the carburetor until I could hear the gasoline bubbling inside, then crank the car, the motor would start. We had very few garages at that time and head-bolt heaters were unheard of. The heaters were of poor quality, so freezing during a car ride was quite common.

“I would say that I probably suffered less in the Model T than in any other car I had at that time. The floor boards were usually open around the foot pedals and the hot air from the motor was always coming up — a blessing in the winter and a nightmare in the summer.”

dramatized retelling: © 2024 Joyce Holt

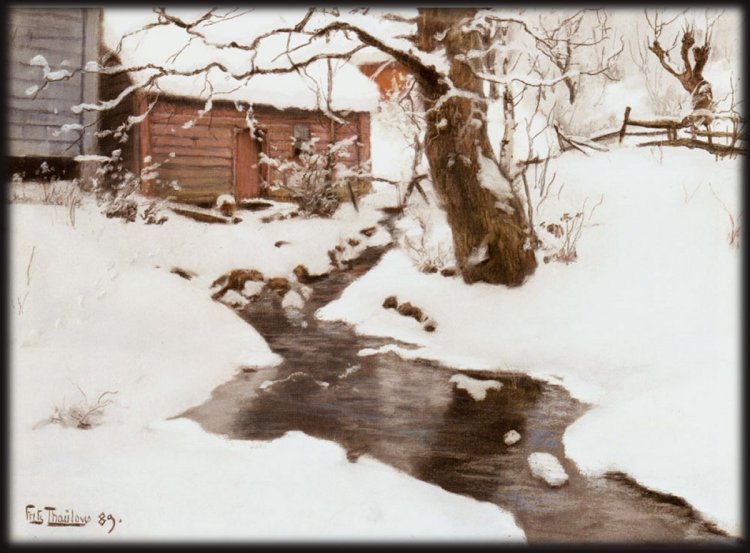

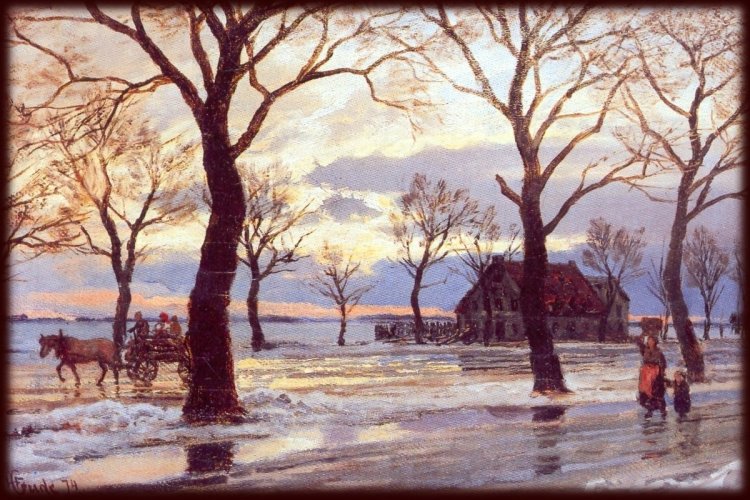

artwork: 19th century paintings. Public domain info here.