WAYNE HAD DRUNK AND GAMBLED clear through the night. He’d cheated. He’d bullied. He’d left the barmaid in tears, the red imprint of fingers on her arm.

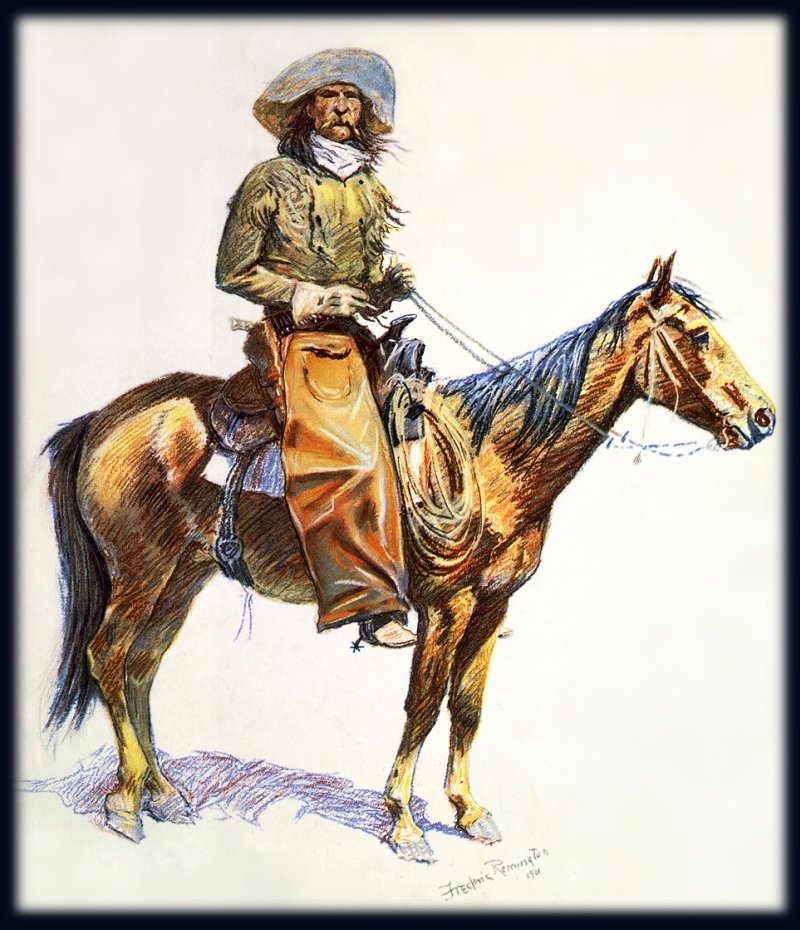

Now he staggered from the saloon, jug of whisky in hand. He ducked his horse’s ill-tempered bite, hauled himself into the saddle, then headed for the road out of town.

On his ride back to the canyon, three times he shook himself awake to find old Coot grazing off the path. Spurs and whip used with abandon got the cowpony moving again, with many snorts and insults on both sides.

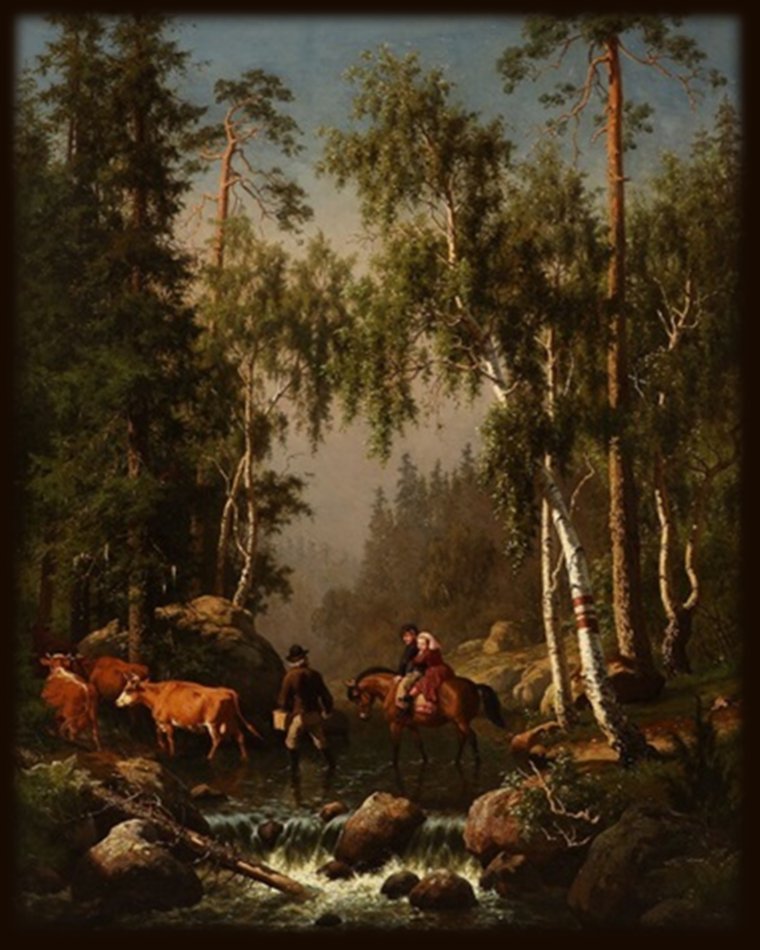

No such luck when they came to a stream moseying down from the hills. When Wayne wouldn’t let the cowpony drink, Coot bucked his rider clean off and refused to budge till he’d gotten his fill of water.

Wayne dusted himself off. Had he forgotten to stop at the watering trough before leaving town? Tough luck.

“You ain’t the only thirsty critter ’round here,” the cowpoke growled as they got back on their way. He started in on his jug. Whiskey would shorten his long trek back to the ranch.

Once again Wayne roused from torpor to find his cowpony rooted to one spot. Cussing up a blue streak he kicked heels hard, but the horse only backed up a pace. The cowpoke fumbled for his whip, but he must have dropped it along the trail.

His brain cleared enough to notice something off. Coot quivered beneath him. Neck arched. Ears flicking all directions.

“Tarnation!” Wayne yelped when he saw they stood at the brink of a cliff.

Backs to the setting sun, their shadows splashed against another rocky wall — the far side of a draw. The steep-sided gully dropped away into darkness. Ahead of them, leaping up from the tablelands, stood a wall of ragged clouds roiling in purple and gold. A growing wind whisked the tang of sage, the twang of coming rain. Lightning flickered afar off.

Coot still wouldn’t budge, even when Wayne urged him to back up. Now the cowpony seemed to gaze up at the clouds. His shiver had turned to shaking.

Wayne gulped. One towering cloud had spilled a streamer that rushed his way, bursting into puffs that reshaped into the form of cattle. A herd thundering straight at him.

Red eyes. Black, shiny horns. Hooves that glinted like steel.

Wayne gasped. Their brands still flickered with flames!

And behind them came gaunt-faced riders, astride horses snorting fire!

The ghostly troop raced past, all but one rider who wheeled about in a tight circle. “If ya want ta save yer soul from hell a-ridin’ on our range, then cowboy, change yer ways this day, or with us you will ride a-tryin’ ta ketch the devil’s herd across these endless skies!” *

The cowpony’s terror broke all bounds. Coot whirled and fled, Wayne clinging to his back for dear life.

Life, dear life. Days, months, years — how long would it take to change his ways truly and deeply?

Based on the country western song “(Ghost) Riders in the Sky.”

* The ghost’s words: from the last verse of the song.

According to songwriter Stan Jones, when he was twelve an old Apache (?) from Cochise County, Arizona, told him of his people’s belief that after death your spirit rides like a ghost in the sky.

Later Stan told this to a young friend, and they sat looking at clouds, finding shapes like ghost riders.

Years later Stan wrote lyrics based on this idea — and echoing old European myths of the Wild Hunt.

“(Ghost) Riders in the Sky” timeline:

– 1926: inspired by a legend heard around this time

– 1948: written

– 1949: first produced, to be performed by many artists including Burl Ives and Bing Crosby

– 1979: Johnny Cash’s release of the song

“Members of the Western Writers of America chose it as the greatest Western song of all time.” (Wikipedia)

text: © 2022 Joyce Holt

artwork: 19th and early 20th century century paintings. Public domain info here.