SVEINUNG MÅNEKOSI TOOK A DETOUR from his trek. Not very neighborly to go skiing past Stykkje farm without stopping to give greeting. Besides, Kari Stykkje owed him a drink of brandy after the rounds he’d footed last time at the tavern.

Sveinung skidded into Stykkje’s farmyard. “Halloo!”

Kari appeared at the cowbarn doorway. “Sveinung! Just the person I need. Come into the house for a dram.”

He knocked off his skis, unlaced the bindings, doffed his top hat and followed her in.

“Where are you headed?” Kari asked, pouring the brandy.

“To Seljord’s shops. The missus needs to restock the larder.” He drew out the reminder list. Oatmeal, barley, dried peas and coffee.

“While in town,” Kari said, “could you swing by the churchyard and fetch me a bag of hallowed dirt? There’s something ailing my cows. I think they’re under a curse.” She grimaced.

“Graveyard soil, ja sure, I’ll fetch you some.” Sveinung grinned, though he silently scoffed at her superstitions.

Kari gave him a small burlap sack. He folded it a couple times. No room in his pocket, stuffed with the money pouch. He crammed the burlap into the tall crown of his top hat, jammed it back onto his crown, bade her farewell and set out.

One more short detour. Aanund’s inn at Eide lay midway along the fjord. Time to be neighborly again. Besides, Aanund’s inn included a bar stocked with some fine brandy.

Several jolly fellows sat there drinking.* Sveinung cheerfully ordered a round for everyone.* He could afford it, and they’d all eventually repay him in like manner. Besides, it’s poor form to be stingy, right?* A dram or two does a body good.*

Two or three drams more, and five or six.* From each shot he ordered for another, he tipped a dribble into his own glass,* so the money was doubly well spent.

Next thing he knew, Sveinung was waking up in the dark. Head pounding, guts lurching. He winced, scrabbling around in the bedstraw, struggling to his feet, cracking the door. Where was he?

In a storeroom at Aanund’s inn. In morning light. What was he doing here? Oh ja, on his way to the shops at Seljord.

From his pockets he drew the crumpled list and an empty money pouch.

Empty? Had he spent it all on drink? He gulped. He was going to catch it from the missus.

He dusted off his hat – and out fell the burlap bag.

Rotten luck. Now he’d have two women cross with him. Go on to Seljord just to fetch graveyard soil? Not on your life.

Sveinung grinned. He could appease one woman, at least.

Hours later he stopped in at Stykkje, swinging a bag full of cowbarn dirt. A minor deception to mollify her superstitions.

“I knew I could count on you!*” Kari lauded Sveinung with praise and another dram of brandy.

Her spirits dampened, though, for her cattle did not improve. And back home at Månekosi, Sveinung’s cows, one by one, fell ill.

* lines straight from the tale; folktale from Seljord, Telemark, Norway

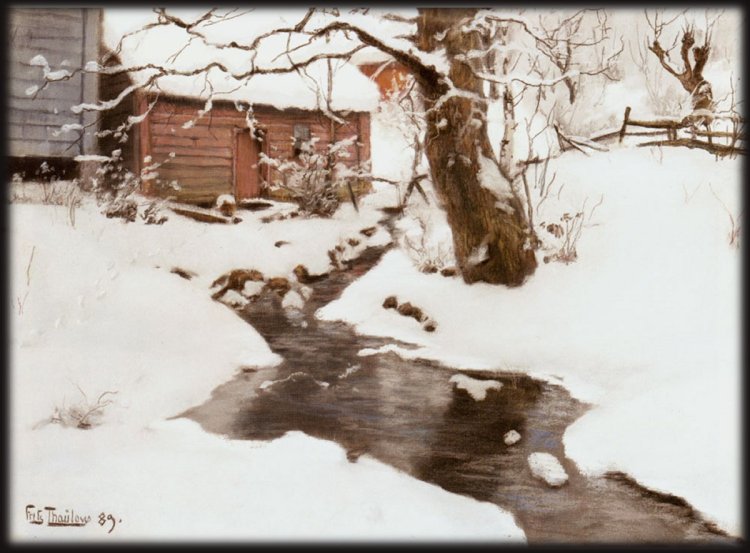

Sveinung Månekosi was born in Seljord in 1800.

text: © 2022 Joyce Holt

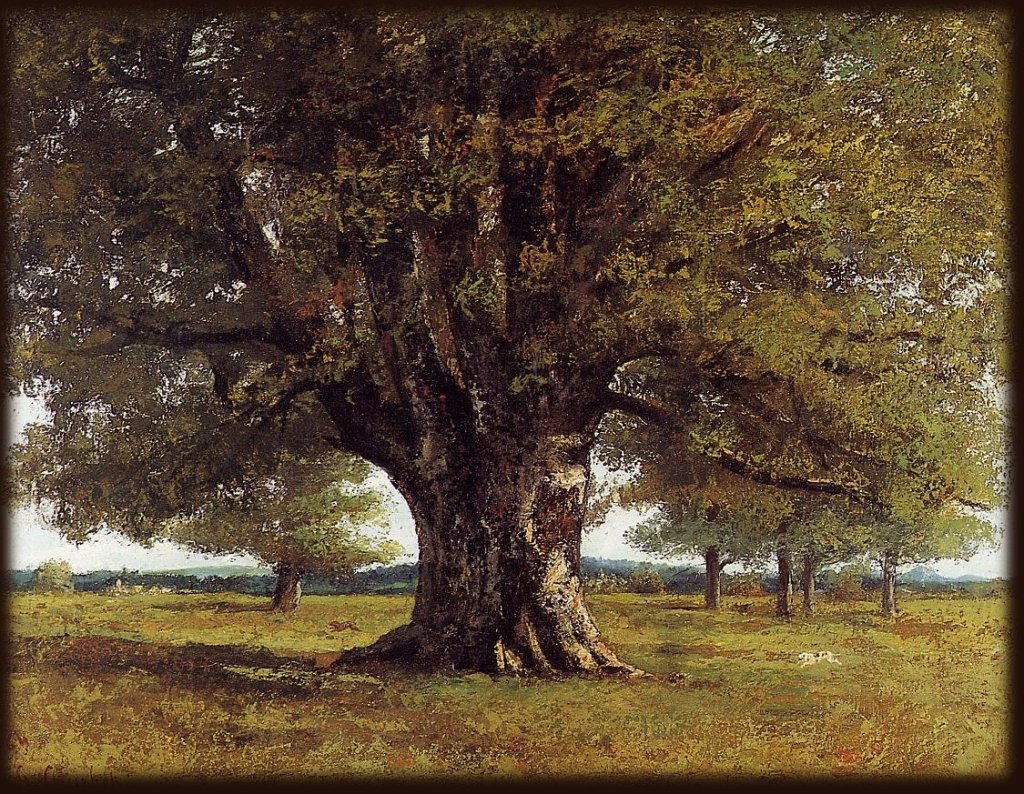

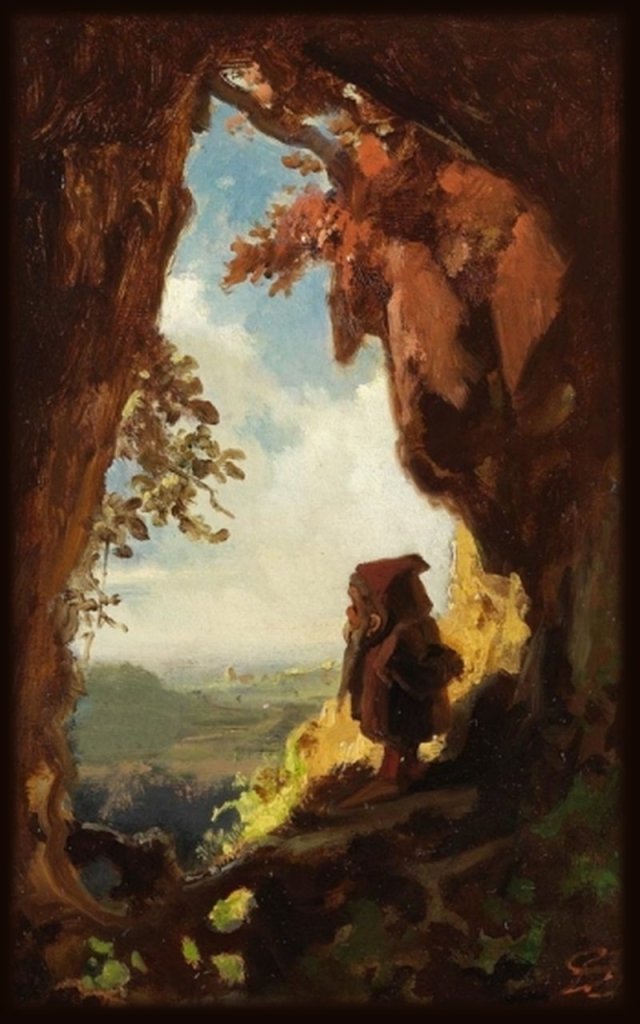

artwork: 19th century painting. Public domain info here.