ISN’T THAT ENOUGH?” Norval called.

“No!” Richard yelled, running ahead to Badwater Creek.

Norval and Lawrence followed with all the buckets.

It only took one smash of Richard’s pickax to shatter the skin of ice that had already formed over their dipping hole. “Come on, hurry,” he barked. He filled his buckets and lugged them back up the bank.

Norval and Lawrence grumbled at the cold but followed orders.

“This track needs more, over here,” Richard said.

Norval swung his buckets as he crossed the first rail. Water slopped onto his canvas trousers. He shuddered at the frigid bite of soaked cloth against his skin.

The three twelve-year-olds poured creek water over the ice formed by earlier bucketfuls.

“Where we gonna hide?” Norval asked.

Richard pointed up the gentle slope. “Behind those sagebrush clumps. A perfect blind!”

He should know. Norval envied his friend’s hunting skills. Richard Comas could bag a rabbit with just one shot.

The friends hunkered behind sagebrush. Norval stuck hands into armpits to try to thaw them out. Gloves didn’t do much good when sopping wet.

From their hiding spot the boys could just see the roundhouse across the creek and down a ways. They didn’t have long to wait. Richard knew his father’s schedule well.

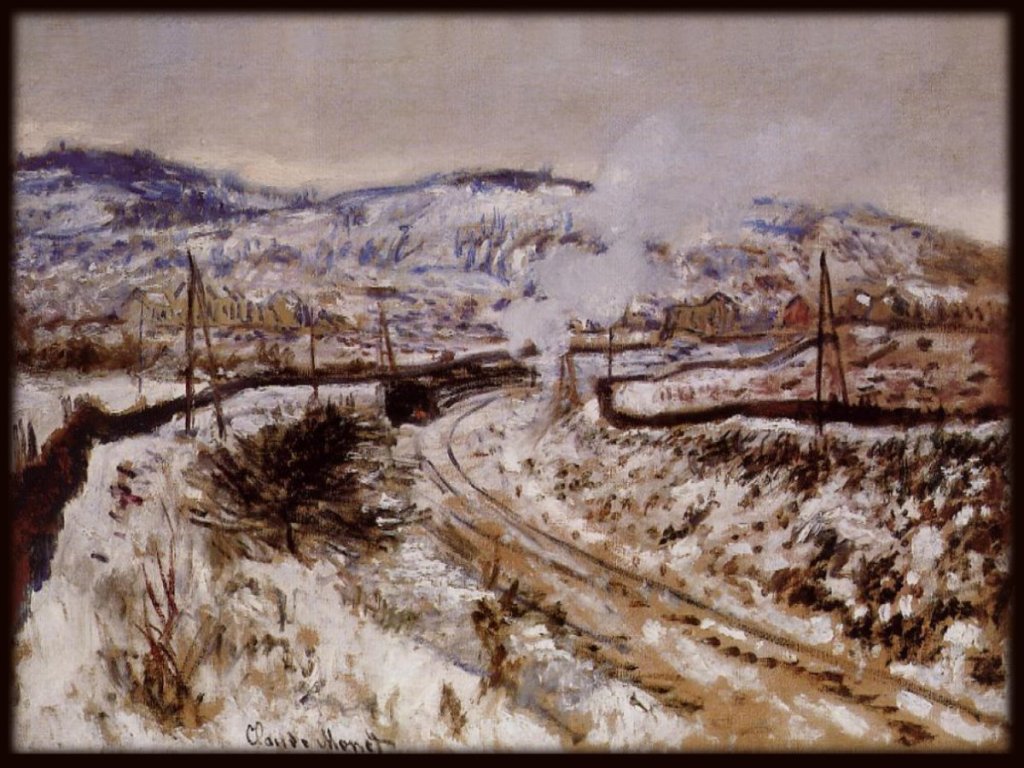

Smoke plumed from the roundhouse’s gaping doorway. Chuffs sounded, crisp on the icy air. A steam locomotive nosed out of the shadows. It moseyed into position, merging onto one of the side tracks, then backed to a long string of cars. Couplings clunked and clattered.

Smoke billowed. Wheels screeched on metal as the iron beast leaned into its task and slowly built momentum.

“Here it comes!” Richard crowed. No need to keep voices down, not with the racket of the approaching train.

The locomotive crossed the trestle over the creek and began laboring up the gentle slope, a powerhouse dragging a long, burdensome string of cars. When the steam engine reached the ice-encrusted rails, though, it lost its grip. Metal slid uselessly on ice.

“Lookit them big wheels spin!” Lawrence laughed.

“And hear ’em roar!” Norval added. That locomotive was going nowhere.

The engineer, Mr Comas, leaned out for a look at the rails, then shrugged.

“Now watch this!” Richard cried.

In Norval’s own words: “His father pushed a lever in the cab of the engine, and it dropped a stream of sand on the rails in front of the big spinning wheels. The sand digging into the steel wheels and rails shot out behind a shower of fiery sparks. Then the train picked up speed and went on to Casper. Richard’s dad waved to us! He knew what had happened.”

Another story from my father’s childhood in rural Wyoming in the early 1940s. This took place a few miles northeast of Shoshoni at the tiny train town of Bonneville. My father lived on a homestead about 12 miles to the north, within reasonable biking range for a rural youngster. Casper lay 100 miles to the east. Steam engines were still in use until the 1950s.

text: © 2023 Joyce Holt

artwork: 19th century paintings, listed as in public domain. Public domain info here.