OLD TORGON PATTERED UP THE FOREST PATH, her grandchildren trailing behind. Birdsong rang into the early dawn, twining with the youngsters’ piping voices.

“Hush!” Torgon hissed as they broke into a clearing. “The tusse-folk hereabouts no longer put up with idle chatter.”

“Did they once?” her granddaughter asked. A basket of cloudberries swung from her arm.

The old woman nodded. “My good friend Maren would jest with them all day long, but then, she also showed them the proper respect. As shall we. Come along.”

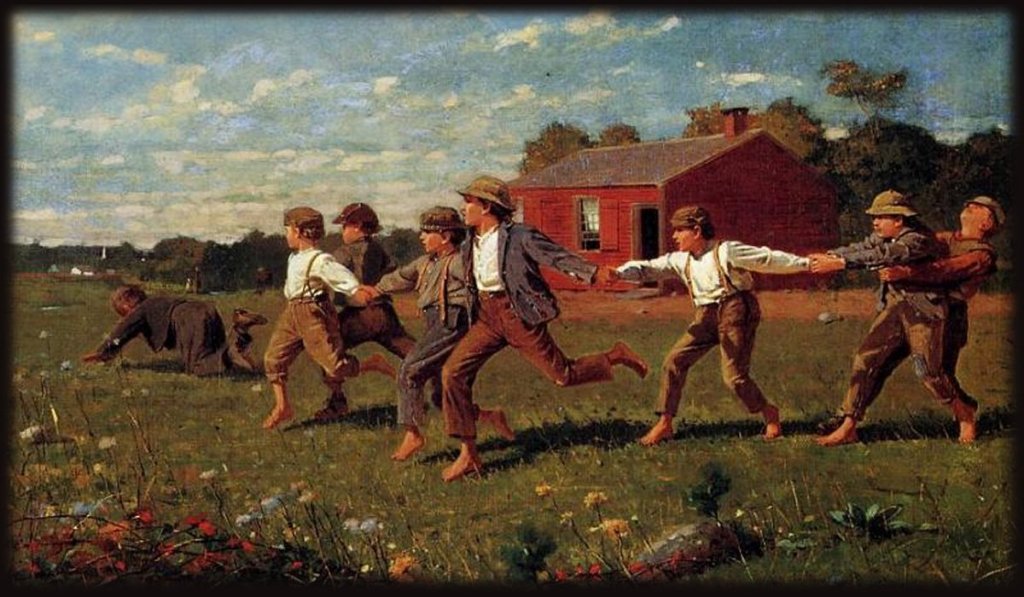

“But everyone else is going up the other trail,” the grandson said. He climbed a stump to watch the procession of men with axes.

“We’ll go there next. Do you still have cream, or have you jostled it into butter?”

The boy slid back to the path with the crock held high. “It’s still sloshing.”

Torgon led the way to a hulking, gnarled oak. She set down a bowl on a smooth granite slab between the roots.

The boy filled the bowl with the traditional offering to otherworldly folk.

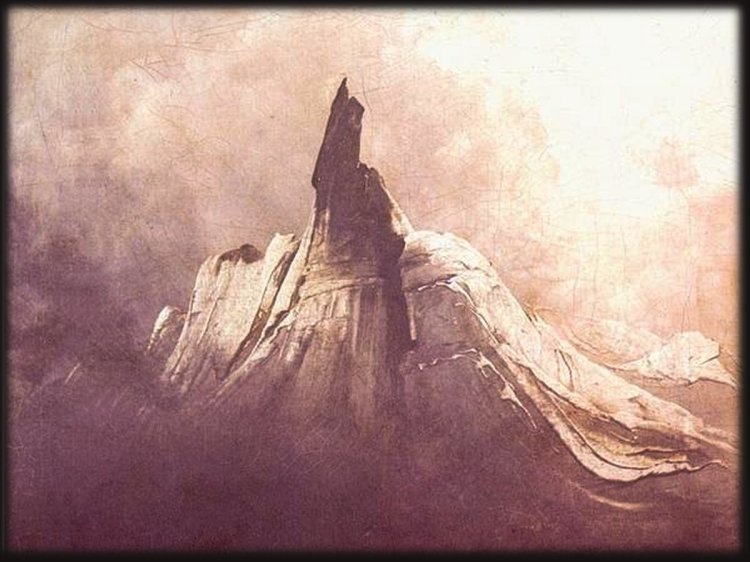

Then the three hurried along and caught up with the work party. In a clearing higher up the mountain, the men stopped to gaze at yesterday’s work, all torn down and strewn around.

Søren Oleson, the new owner of Uvaas lands, had laid stone slabs for good footing. Next he’d affixed massive timbers as a base for the cabin. He’d built the walls with finely set logs and started on rafters. Started more times than he cared to count. But every night the angry tusse-folk had thrown down the timbers and uprooted the flagstones.

Torgon and the children settled on a log to watch.

Søren ordered the men to task. “If we can build it to the rafters in one day,” he declared, “and hang a cross, surely it will stand against mischief.”

“That’s the man,” Torgon told the youngsters, “who didn’t believe in tusse-folk at all when he moved here. Now he challenges them outright. Hiring an army of helpers!” She tut-tutted as she spread a blanket, set out her stack of flatbread and a tub of butter.

The granddaughter placed her basket of cloudberries. “Hungry helpers!” she giggled.

Torgon sniffed. “I warned him it was a useless endeavor, but he insisted. At least he paid in advance.” She jingled her money pouch.

Through the long day the old woman fed hungry lumbermen. The cabin grew before their eyes. Chest-high. Head-high. Loft-high. Rafters went up, then the roof structure – slats, thick layers of bark, strips of sod.

As daylight faded, Søren went to nail a cross under the roof’s peak.

The ladder broke, tumbling him to the ground. The cross shattered. The head flew off the hammer.

Twilight turned eerie, threatening. Men backed off, muttering and making countersigns against evil.

“Time to go,” Torgon chirped, leading the children home.

That night, once again, the mountainsides echoed with the clamor of timber and stones flung around.

Søren gave up at last and moved away.

folktale from Uvaas farm, Hjartdal, Telemark

text: © 2022 Joyce Holt

artwork: 19th and early 20th century paintings. Public domain info here.