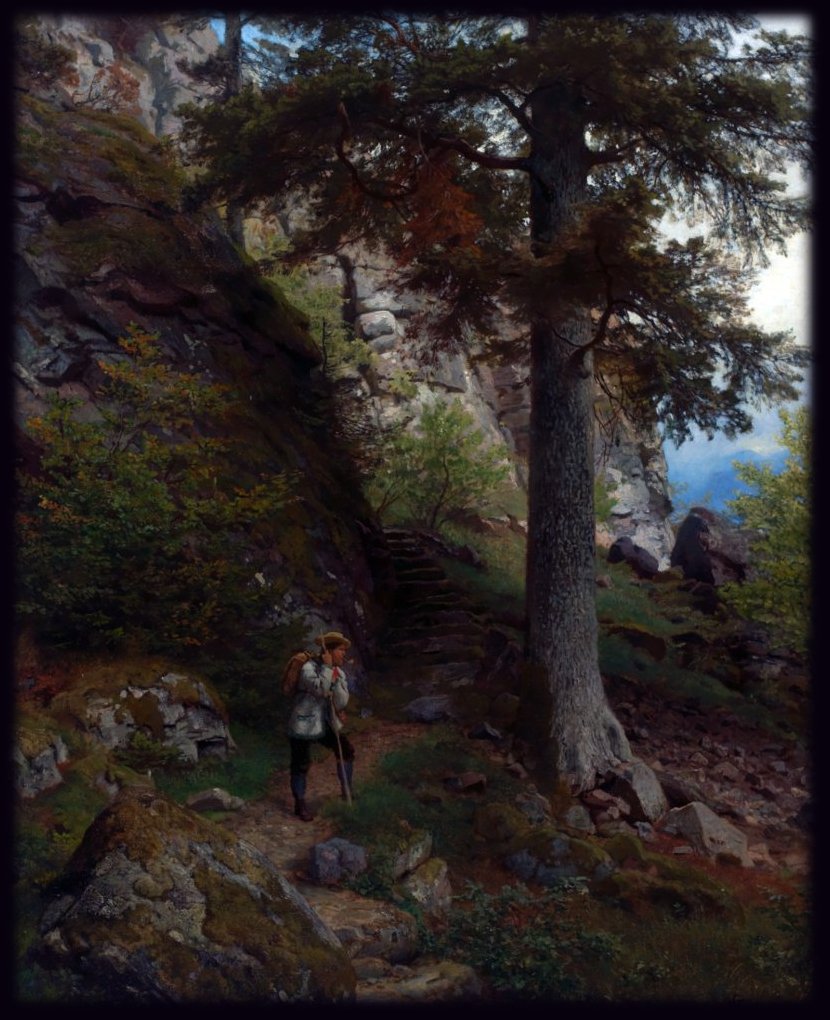

EVEN THOUGH LARS SET A GOOD PACE down the mountainside, he couldn’t outrun dusk. Night fell as he approached the most treacherous stretch of the trail. He slowed his gait, peering ahead in the gloom.

It didn’t help that the melke-ringe he carried was so heavy and cumbersome. The wide, shallow, wooden vat unbalanced him. The sour odor of fermenting milk still clung to the slats, twanging against the sweet scents of spruce and pine.

Lars set the melke-ringe down at the foot of a cliff, and sank down on a boulder to rest. The moon would rise in an hour or two and light his way home to Veslestoul.

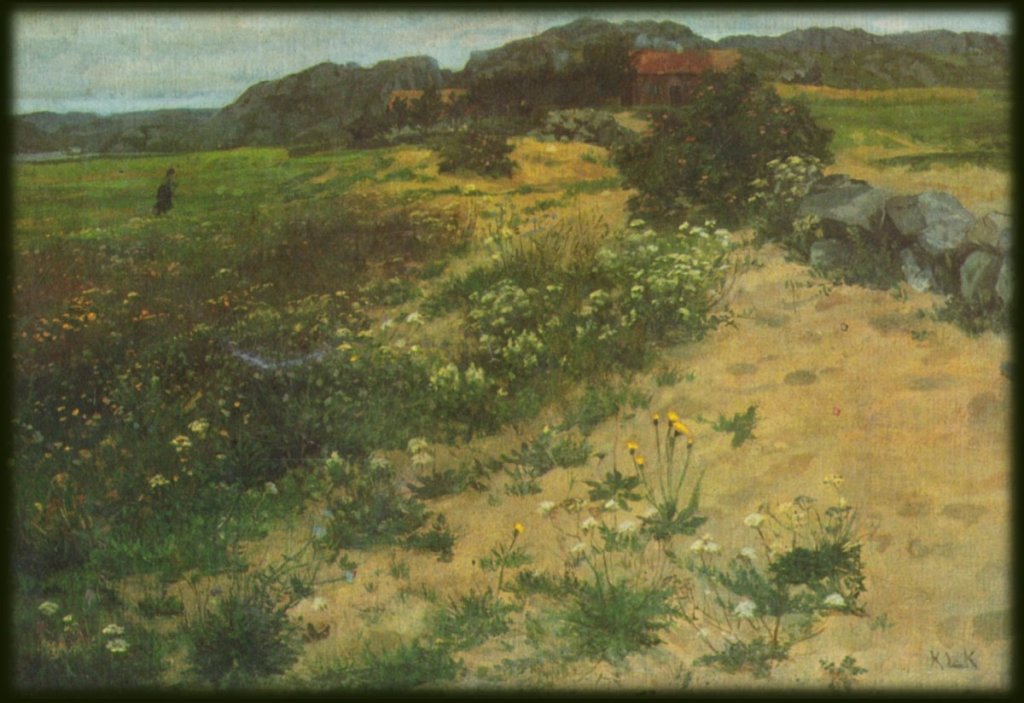

He shook his head at his folly, lingering so long at the high mountain summer farm of Staalstoul. But his sweet tongue had talked down the price of the vat by several copper coins. And before long he’d save even more by making his own clabbered milk rather than buying from a neighbor.

Other wanderers might have stayed wide awake and alert in this haunted forest, but Lars had grown up here, no stranger to the wild tusse-folk who roamed the fjells. He yawned, leaned against the cliff, and dozed off.

Voices nearby. Close, crisp, laughing.

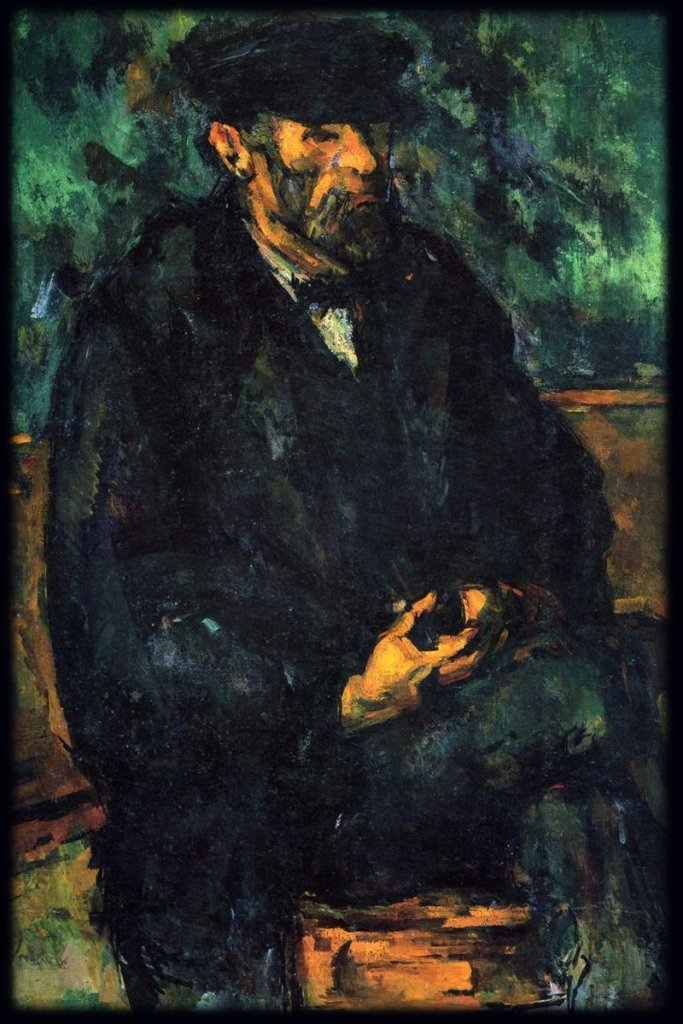

Lars snapped awake, and found himself inside a warm and cozy dwelling – filled with tusse-folk. An old man, an old woman, a whole flock of youngsters. They greeted Lars with good cheer and offered him food and drink. Others might have feared to partake, but not Lars. He drank the ale and spooned up the buttery porridge, sweetened with wild honey.

“Thousand thanks!” he told his hosts as he wiped his lips. “Delicious fare you so generously offer to a weary traveler. I’ve never tasted better. But now I must be on my way. Must haul this old melke-ringe home in time for the morning milking.”

The old fellow clapped Lars on the back. “One of my strapping big sons will follow you home. He’ll carry the tub, and spare you the bother.”

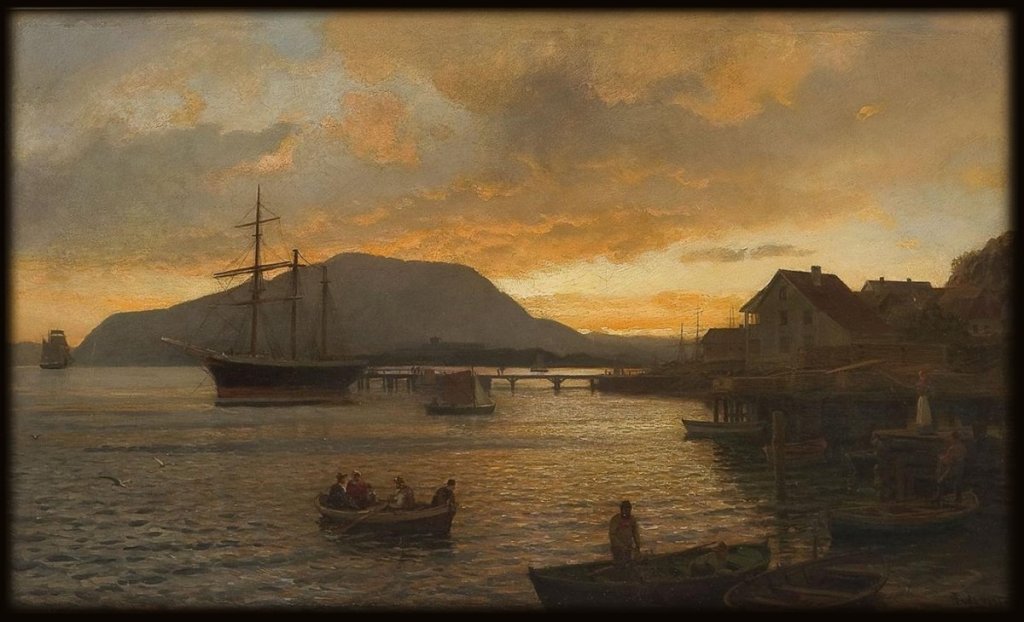

Next thing Lars knew, he was waking with the dawn, inside his log cabin at Veslestoul, and the melke-ringe sat upon the table.

folktale from Veslestoul, Lidfjøll, Telemark

text: © 2022 Joyce Holt

artwork: 19th century painting. Public domain info here.