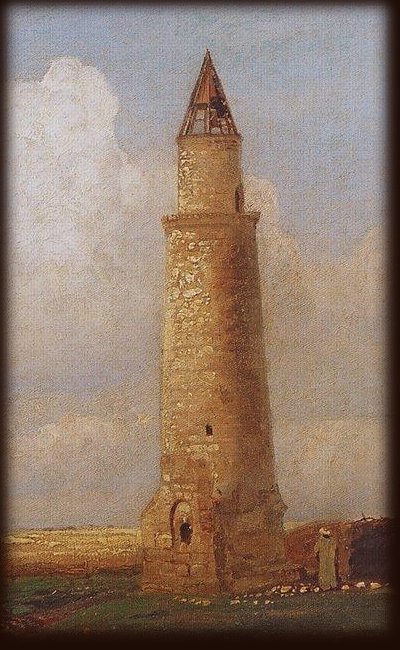

UPON A ROCKY HEADLAND on the coast of Normandy

a mighty tower of stone stood ever watching out to sea.

In the shadow of the tower, where the seaward breezes blew,

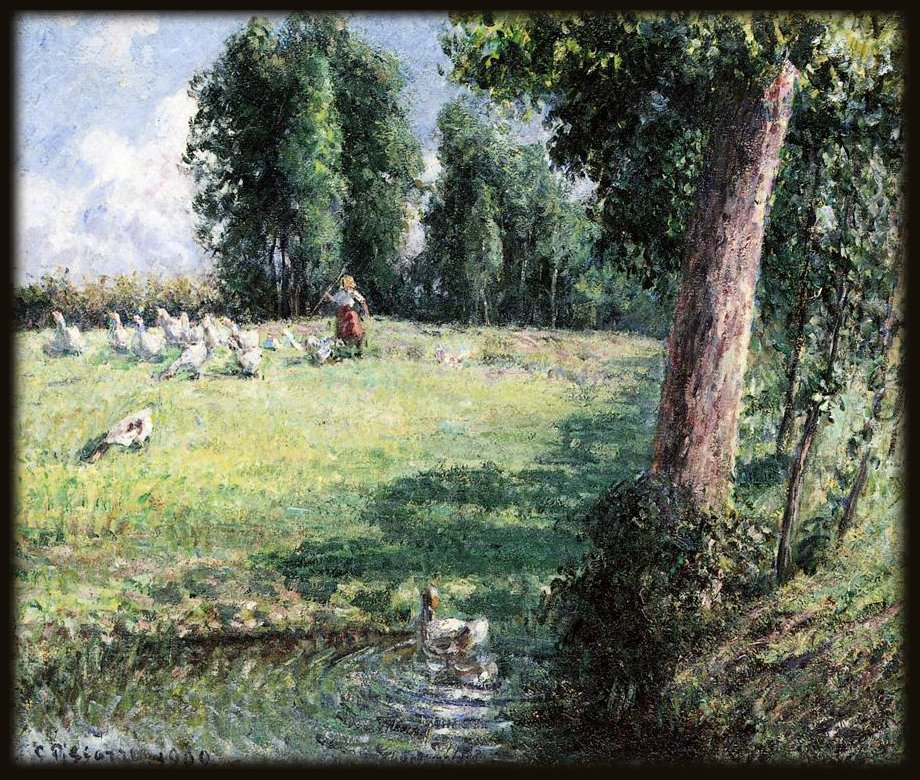

dwelled the gentle-hearted people of the fishing town Pirou.

One day the tower watchman felt a sudden lurch of dread

for from the north sailed Viking ships, each prow a dragon-head.

Broad sails for wings, the dragon ships sped swiftly over the waves.

The loot these raiders sought for wasn’t gold but human slaves!

The village folk in panic gathered ’round their Druid sage.

The old magician riffled through his lore-book page by page,

then off they dashed together to seek refuge in the tower

and there the wise man read aloud the ancient words of power.

The tower’s oaken gate withstood the batter of a ram —

but not the bonfire kindled at the foot of door and jamb.

The flames gnawed deep, and deeper still. It seemed a certain doom!

Through smoldering beams the Vikings leaped — into an empty room.

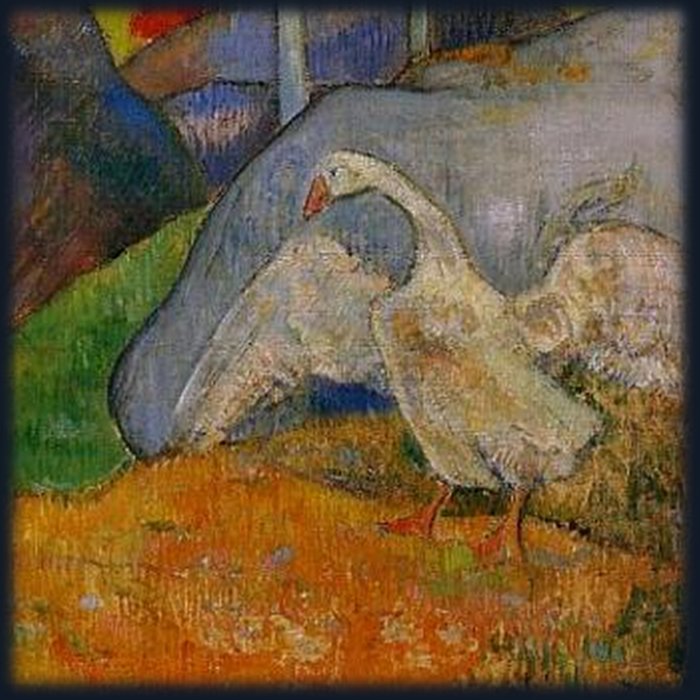

Transformed by sorcery to wild gray geese, the folk took flight.

Through window-slits they flurried to escape their dreadful plight.

The Norse berserkers raged and fumed and lived up to their name

and set the town and tower of Pirou to axe and flame.

A fate of ash and cinders for the book of magic lore!

The spell to dis-enchant the geese was lost forevermore.

Above the ruined tower, soaring through the autumn skies,

you still can see the wild gray geese and hear their mournful cries.

My translation of lyrics of a Norwegian song produced in 2004.

A straight-across translation is called a “derivative work,” and copyright remains with the original writer.

However it took particular skill to render the song poetically in a different language. It wasn’t just phrase by phrase translating. If this qualifies my lyrics as “transformative work” inspired by, rather than derived from, another person’s creation… then I can claim copyright.

transformative text: © 2023 Joyce Holt

artwork: 19th century paintings. Public domain info here.