THE TRAVELER COUNTED OUT THE COINS, then cocked a brow at the innkeeper’s wife. “You’ve shorted me on my change, madame.”

Megan snorted. “I have not. You ate three meals and had three pots of ale, plus two nights’ lodging.”

“Two meals and one pot only.”

“Are you calling me a liar?” Megan hissed.

“A cheat.”

Megan squawked loud as any barnyard fowl. “To my own face, is it? I’ll have my husband throw you out!”

The traveler donned his wide-brimmed hat and shouldered his bag.

“I’ll not have you slandering me on my own premises!” the woman blared, jutting her head and flapping arms at him.

“Now love,” the innkeeper said. “I can hear you honking clear out in the stables! Calm down.”

“Honking, is it?” she shrieked, spraying spittle.

“Indeed it is,” the traveler said. He flicked his fingers at her. “Be the goose you are.”

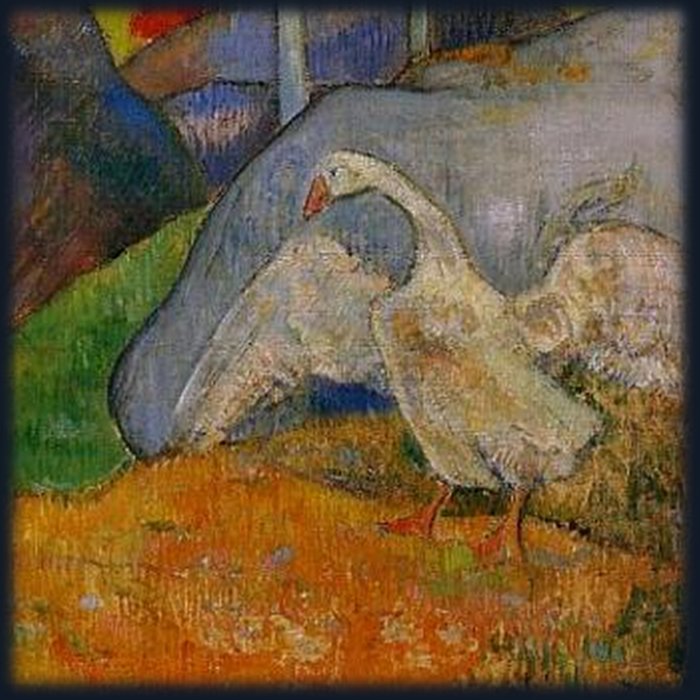

Her gown and apron poofed out as if blown by a gale then collapsed in a pile on the floor. Among the clothing stood a wild goose. It honked and hissed and flapped wings at all the onlookers.

“My wife!” yelped the innkeeper. “What have you done to her?”

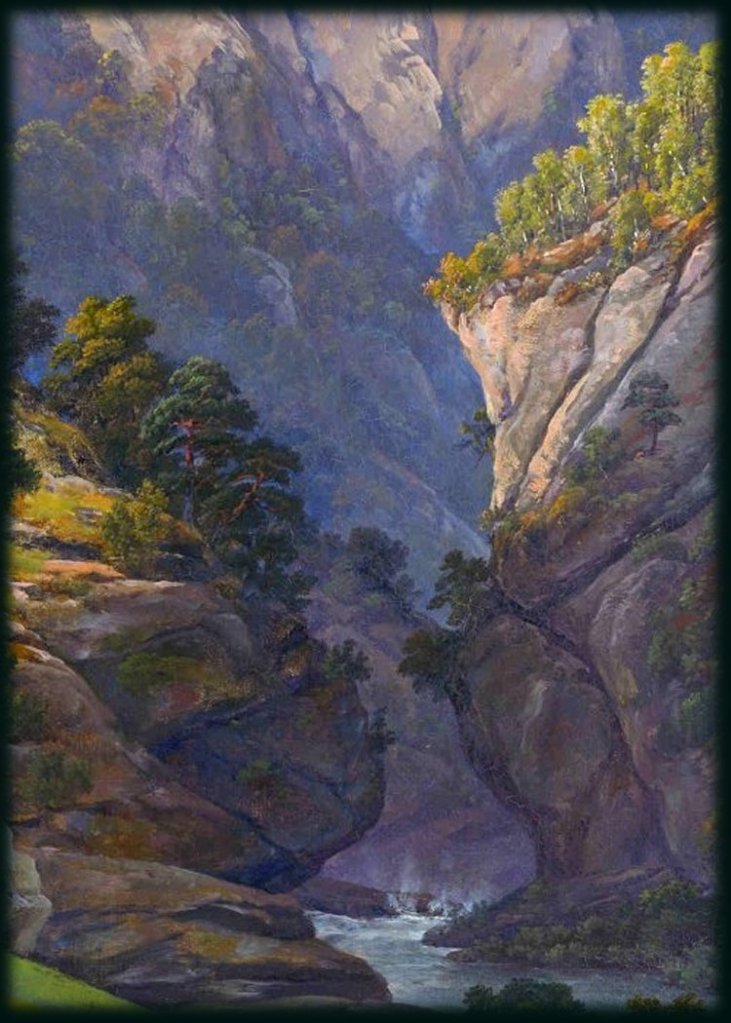

“Simply restored her proper shape. Let all see her for what she is.” The traveling wizard turned to go.

“You can’t leave her like that!” cried the innkeeper.

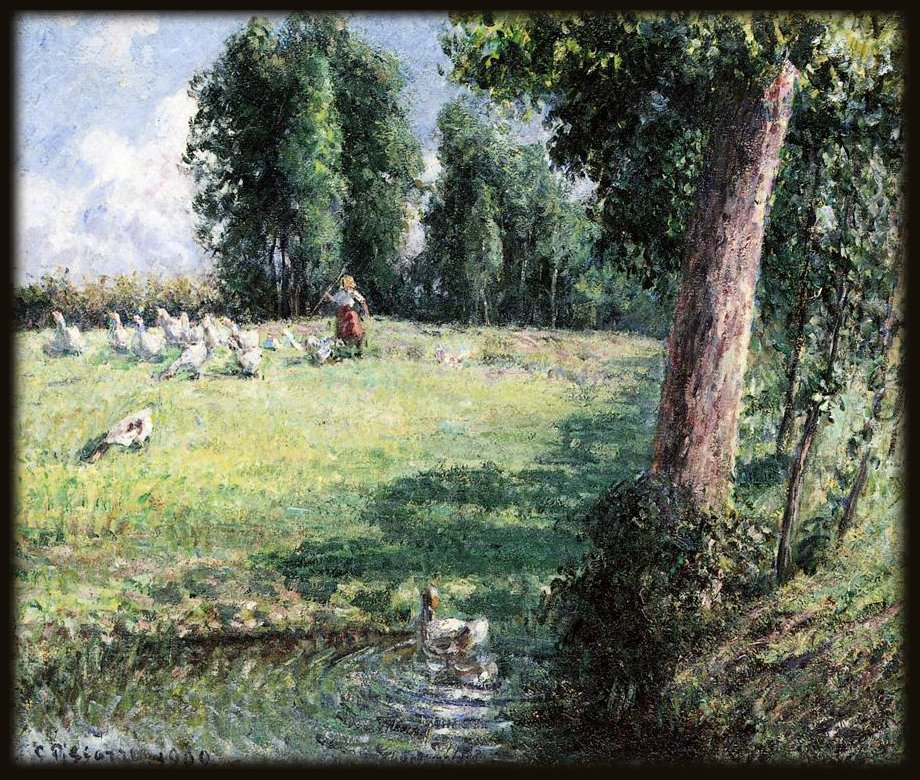

The wizard paused. “True. Michaelmas is coming up, isn’t it? Mustn’t let some poor fellow doom his soul by feasting on your wife. Here, her hair ribbon will do to set her apart.” He drew a ribbon out of the pile, grabbed the hissing goose, and tied the ribbon to one wing. “Bind her tight and keep her safe!” He flicked fingers at the goose as he set it free. “Tell the villagers to leave this one alone.” He strode out the door.

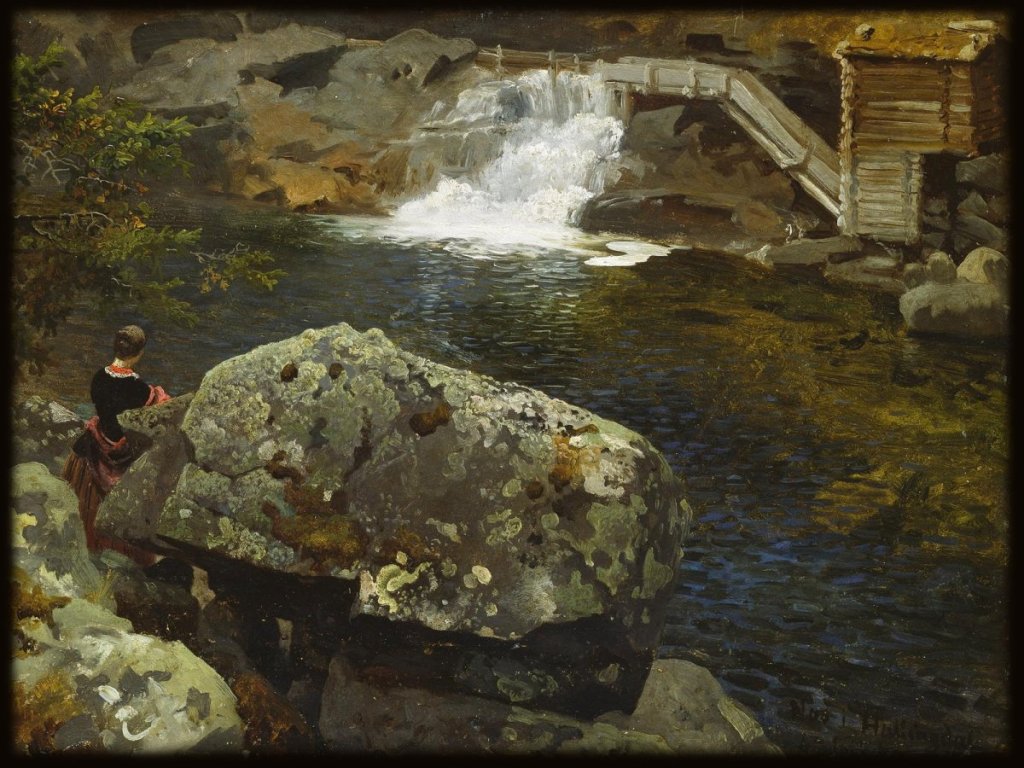

The innkeeper tried to shoo his bewitched wife out to the goose pen, but she bit his fingers and flew away, out of the village, across the fields, and down to the marshes by the beach. There she brooded and sulked.

One lonely day, waddling further up the coast, she came across a flock of wild geese. She joined them for lack of better company.

But better company she did not make. She hissed and squabbled with the other fowl. The day before Michaelmas, when snares and nets had taken three of their number to prepare for the feasting tables, nerves frayed among all the flock. Megan got in another quarrel. She honked and hissed and pecked at the geese closest to hand until, fed up, they attacked her back.

In the melee the ribbon came loose from her wing – and the wizard’s spell broke.

The flock scattered in fright when an angry woman stood up in their midst. She brushed herself off and stalked along the road toward town, not much the worse for wear.

A tale from Welsh folklore.

Michaelmas is celebrated on September 29.

text: © 2023 Joyce Holt

artwork: 19th century paintings. Public domain info here.