BENGT GROPED HAND OVER HAND along the rail leading aft. The gale snarled and raged, heaving the sloop like a monstrous cat playing with a mouse.

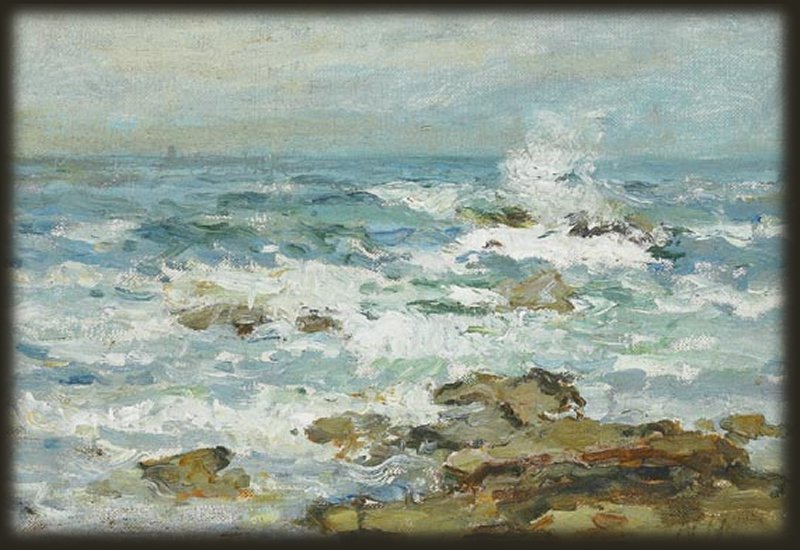

Several times Bengt nearly lost his footing on the slick deck. “I heard a cry of ‘Land ho!'” he called to the sailor at the helm. “Will it be safe haven in a cove or shipwreck on the rocks?”

“You should stay in your berth, Herr Holbek,” Johan shouted from the stern. “You’ll be washed overboard!”

“If we’re bound to break apart, I’m headed for the deep anyway. What does the lookout say? Any idea where we are?” Bengt saw nothing ahead but mountainous waves. He lashed himself to the rail, tested the quick release of the knot, then tied again.

The sloop slid sideways into a trough, keeling to the side. Johan wrestled the tiller until the ship grudgingly heeled about to plow head-on into the coming billows. “Thought it might be Røst, our last chance. But no, lookout says it’s too low.”

“Have we been blown past Røst in the storm?” Bengt asked.

“No way to tell, with the compass smashed. Whatever it is, if we can work our way around, we might find shelter in the lee.”

Bengt wiped sleet from his face and peered again into the murky rain veils ahead, swirling in heavy hues of grayed purple and slate blue. They had warned him, back in Bergen, it was late in the season to voyage north.

But they’d had clear sailing past Trondheim, such fine weather that the captain reasoned it a good risk to set out across open ocean, heading for the Lofoten Islands.

In autumn, how quickly the weather changes.

Bengt straightened and stared at a glimpse of emerald green through the dark shrouds to port. “Did you see–” he began.

Voices clamored on the wind. The lookout. Other sailors. Then the captain shouting orders.

Johan hauled on the tiller, guided the skittish sloop into the calm waters of a bay.

Bengt gaped at the sight. Beautiful green-and-gold meadows sloped down to meet the sea. The low island seemed to curl around the harbor, unruffled by the storm howling past in the heavens.

A chain rattled as they lowered anchor. Bengt untied his safety line and joined the sailors along the rail, staring at the shore where barley grew thick and golden as the pelt of a fox. The field didn’t end at water’s edge, but continued underwater. Bengt leaned over the rail and gazed into the depths where barley still thrived, waving with the current.

No one suggested going ashore.

At last the storm broke. As sailors labored to haul the anchor aboard, the land began to sink. The whole island vanished beneath the waves.

The crew halted all movement, everyone staring at the anchor dripping on the deck, ready for stowing. It was twined with barley ears. The barley of Utrøst, the hidden island of bliss.

Good luck followed them until their journey’s end.

Folktale from Tysfjord, Ofoten, and Lofoten, Nordland, Norway

text: © 2022 Joyce Holt

artwork: 19th century paintings. Public domain info here.