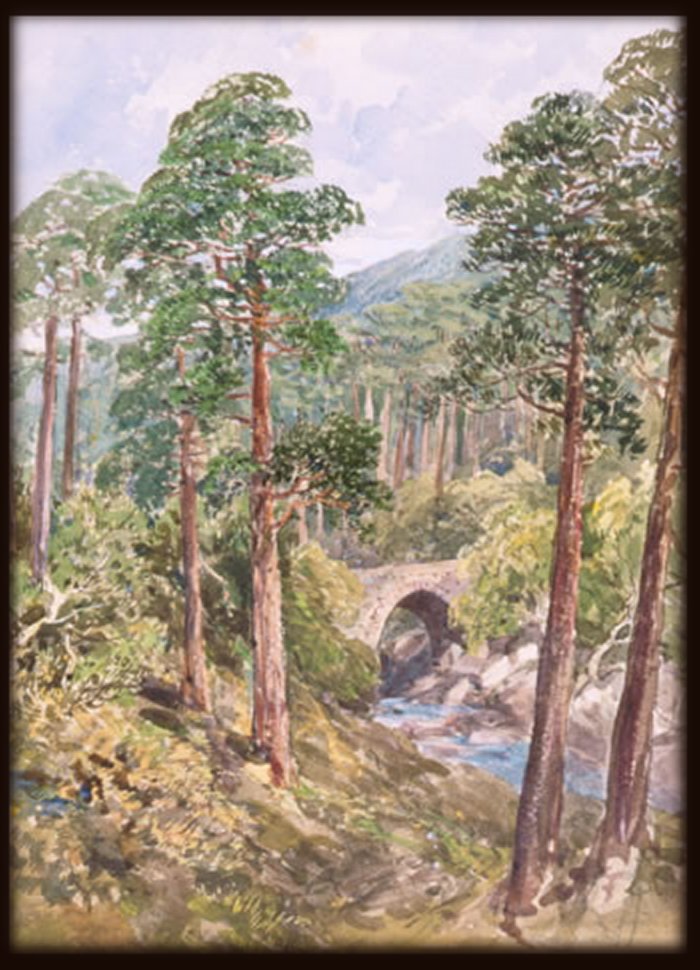

ALFGIFU POINTED THROUGH THE UNDERBRUSH. “I see a hazel tree.”

“Not just one.” Rothmund ran ahead, lugging his bucket. “A whole grove! We’ll find plenty of nuts here.”

“What story shall I tell while we gather?”

“Beowulf!”

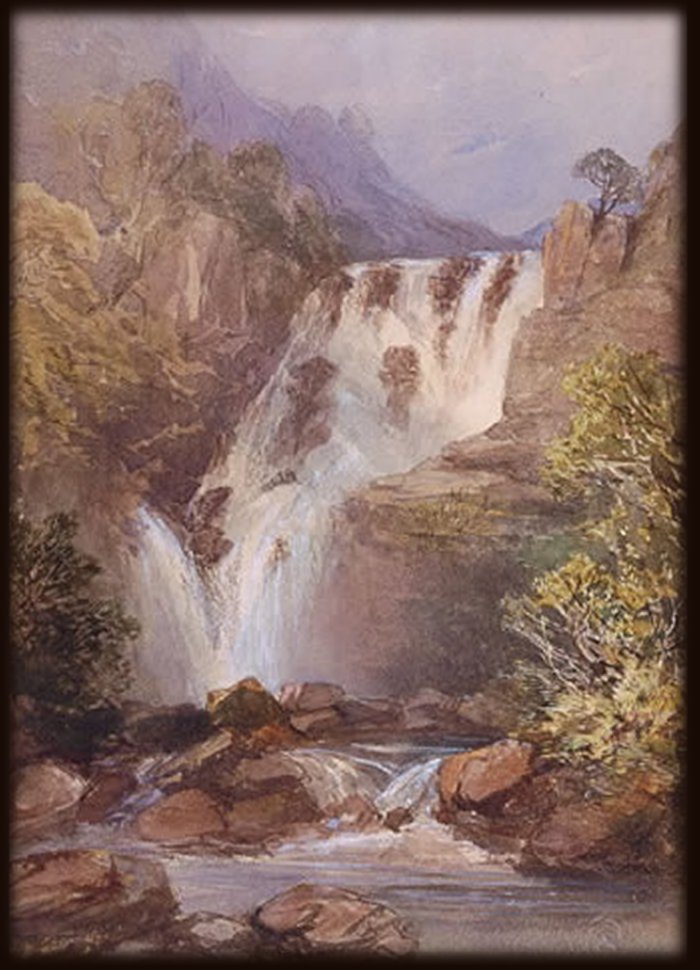

Alfgifu launched into the tale while they scuffed through duff beneath the trees, hunting for hazelnuts. “News spread far and wide about the troubles of King Hrothgar of the Dane-Mark. Every night a horrid monster rose from the marshes, broke into the king’s hall, and carried off a warrior to devour. None could stand against Grendel the terrible.”

“I bet I could have!” Rothmund tossed another handful of nuts into his bucket.

“Perhaps when you’re full grown.” Alfgifu went on with the tale about the young hero from across the channel who came to the aid of his father’s friend. When Grendel next attacked, Beowulf fought the monster. By incredible strength the unarmed hero ripped Grendel’s arm from his body. Now who was unarmed?

The monster fled back to the swamps, gushing its lifeblood with every step. It plunged into the mire and never rose again.

“Hrothgar’s hall rang with celebration for three days,” Alfgifu said. “The monster’s arm hung from the rafters, a gory trophy. Everyone thought their troubles were over. But the next night–” She broke off, turned, listened.

“You can’t scare me, sister!” Rothmund said. “I know what comes next. Grendel’s mother!”

Alfgifu cried out, “Danger! Up the tree, now!” She pushed him toward the sturdiest of the hazel trees.

He giggled as he climbed. “She was a huge, big monster. How high must we climb to get out of her reach?”

“This is high enough. Look!”

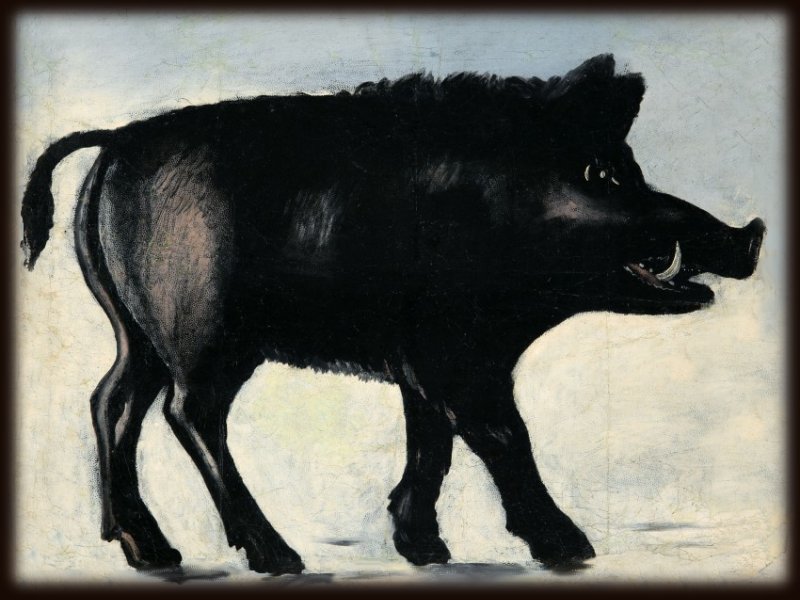

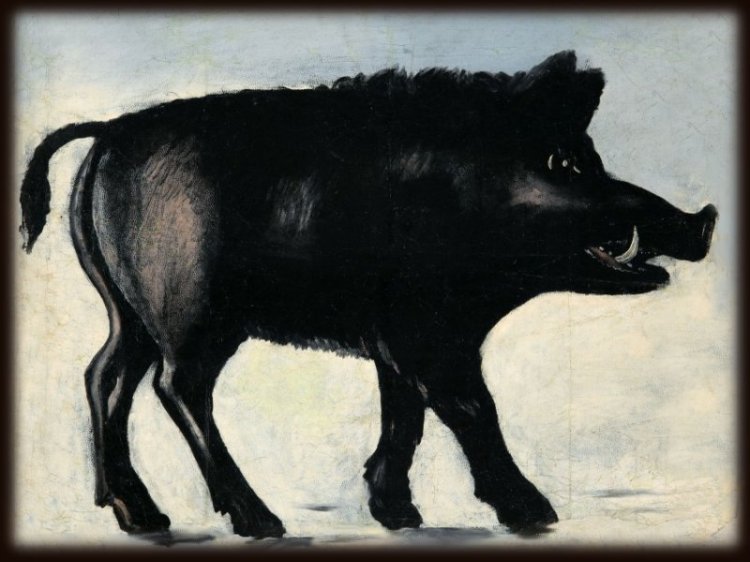

A mob of wild boars burst from the brush, jostled, snorted, rooted in the duff.

“Hey! We weren’t done! They’re going to get our nuts.” Rothmund started down.

Alfgifu grabbed his arm. “Remember the scar on Papa’s leg? These Grendels might be small as calves, but they’re vicious, and you don’t even have a boar-spear.”

“I’ve got a knife!”

“So do the boars. See their tusks? They’d rip you open, like Beowulf ripped Grendel’s mother!”

“When will it be my turn to fight a monster? I want to be a hero, too!”

“You don’t have your man’s strength yet, Rothmund! And when a young hero-to-be doesn’t have might, he must use wits instead. Now be wise. Sit down. Want to hear about Beowulf and the dragon?”

“No.” He pouted.

“Or about Hengist and Horsa with their sleek longships, bringing the first Angle-kin here to Englaland?”

“No! Boring.”

Down below, two pigs scuffled, squealed, fought over a nut. Rothmund’s eyes widened at the sight of blood spilling.

“How about this.” Alfgifu showed him how to carve his name. While he worked, she kept an eye on the boars below, teaching him more runes from time to time.

The boars finally went on their way. Alfgifu stretched. “Now we can climb down and hurry home! Papa and Mama will be wondering where we are.”

“Read this first.” Grinning, he pointed at the runes carved in the bark.

“Here Rothmund outwaited seven Grendels and their mother.”

“No, no,” the boy sputtered. “That’s not ‘outwaited’ — it’s ‘outwitted’!”

“By outwaiting, you outwitted. Very good, my wise young hero!”

Tale set in Anglo-Saxon England.

Pronunciation of Alfgifu: Stress the first syllable; say the next two syllables lightly and quickly. The unstressed i and u are short vowels. The g is like y in yet. Each f is almost a v.

First posted on Hindsight on June 19, 2020.

text: © 2021 Joyce Holt

artwork: 19th or early 20th century artwork. Public domain info here.