HOPE IT’S NOT MUCH FURTHER,” Norval said. “My legs are cramping!”

“I think we’re almost there.” His brother Lyle steered the little Crosley Hotshot around another bend in the narrow road. The woody scent of cherry blossoms wafted on the breeze, unhindered by any barrier but the windshield. Nothing like a fine spring day to go touring Japanese backroads in a fiery little convertible.

No sooner had the next village come into sight than one tire gave a bang, and the car bucked like a bronco. Lyle wrestled the steering wheel and brought the Hotshot to a stop. “You okay?” he asked.

“Banged my knee, but not bad.” Norval unfolded his lanky frame from the tight quarters of the passenger seat.

Lyle too got out. Both airmen stretched out their kinks, nodded to a flock of children who’d come running at the noise, then inspected the blown tire.

“Good thing you have a spare,” Norval said. He unfastened the tire from the back of the convertible.

Lyle rummaged in the trunk. “Good thing we still have plenty of leave left,” he said. “There’s no jack.”

They gazed down the road at the village. No American presence to be seen. Did they even have cars here?

Lyle turned to the children.

“Good thing you’ve been here long enough to learn the lingo,” Norval murmured.

Lyle rattled off a question, and the children piped up with eager answers. He turned to his brother. “No cars, but they have several fine wagons, if we want to hire one.” He studied the convertible.

Norval joined him. “Bet I can lift it long enough for you to change the tire.” He flexed his biceps.

Lyle grinned. “You’re on!” He got all set and gave the thumbs up.

Norval got a good grip on the back bumper and heaved.

The children shrieked with laughter, and chattered like birds while Lyle swapped out the tires and cinched the lug nuts tight.

Norval lowered the car’s rear end. “What are they saying?” he asked.

“If you’re big enough to lift a car, how will you ever fit inside?”

Norval, ever the clown, bowed to the children, then went through all kinds of contortions to fold himself back into the low passenger seat.

Their young audience laughed and clapped as Lyle started up the Hotshot. With a wave, the two airmen drove on down the road, searching for lodgings for the night.

From the author’s family history: Norval and Lyle served in the American Army Air Corps (later renamed the Air Force), based in Japan during the Korean War. Norval tried to learn to speak Japanese but was advised by one amused young lady not to try again. His mistakes could get him into trouble!

text: © 2023 Joyce Holt

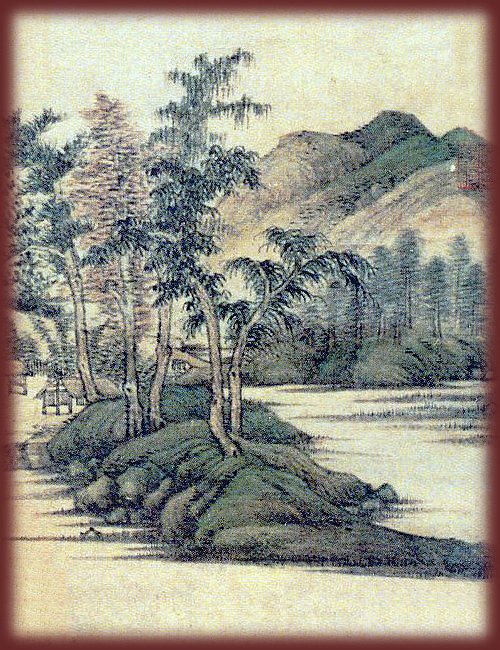

artwork: 19th century painting. Public domain info here.