OLD GYÐJA GOT LEFT BEHIND. Everyone else in Trøllanes piled onto sleighs or sledges and fled the doomed town, but the old woman’s temper had burst all bounds. Every year she argued the townsfolk should stay and fight off the invasion and every year her sons bundled her onto a sleigh against her will, off to refuge in Mikladalur.

Well, not this year. Her sons had not returned from their midwinter hunt in time, and no one else wanted to risk her wrath.

So here she stood in the doorway of her cabin, the only soul left in Trøllanes on the eve of Twelfth Night. Regret for her rashness crept down her spine like icicles.

Midwinter in the Faeroe Islands meant overlong night-time hours and only fleeting brightness near noon. The sun had already set. Dusk swept the icy landscape.

Shadows moved, dark against the snow.

Gyðja stepped out into the courtyard, looked in all directions – and saw countless moving forms, hunched, swaggering, all coming on straight for the village.

The old woman fled back indoors. She barred the door, shuttered windows, and huddled near the woodstove, shaking with cold and terror.

Soon she heard scuffling and tromping in the courtyard, then a rattling of the latch. Gruff voices called and answered. Rough laughter sounded from all quarters.

Now someone pounded at the door until the walls shook. The bars rattled loose from their brackets and clattered to the floor. The door latch lifted.

Gyðja stifled a shriek and dove beneath the table, hoping not to be seen.

The door slammed open. Footsteps came in. More and more, like a flock of sheep crowding into a fold. But those weren’t sheep hooves she saw. Troll feet stomping to troll music. Trolls prancing around, bashing into furniture, knocking bowls and cups to the floor and trampling them to bits.

Every house in the village, Gyðja knew, shook with the tramping and clamor of trolls, corrupting the sanctity of the holy day like they did every year. Trøllanes was cursed in name and in fact!

The old woman clapped hands over ears. She bit her lip to stifle the screams that tried to burst forth.

Toe-claws gouged the floor. Hairy tail-tips whipped past. The wild abandon reached a frenzy. Hulking bodies slammed the table. It reared, about to reveal the huddled human beneath.

The old woman shrieked, “Jesus have mercy on me!*”

That hated name – a blessing to Christians, a cursing to troll-folk – shattered the revelry, splintered the crowd. They peeled away, spilled out the doors and windows. One monstrous voice howled, “Gyðja broke up the dance!*”

The old woman crawled out of hiding and edged through debris to the door.

From every cabin, misshapen forms hopped and trundled and galloped, fleeing town.

A few days later, the first wary townsman came scouting and found Trøllanes vacated. When Old Gyðja stepped into view, he startled and crossed himself. “We thought you were surely dead!”

The old woman chuckled, pointing to clawed footprints in the snow. “I was too much for them!”

The trolls have not disturbed Trøllanes ever since.

* lines straight from the folktale, from Kalsoy in the Faeroe Islands

text: © 2022 Joyce Holt

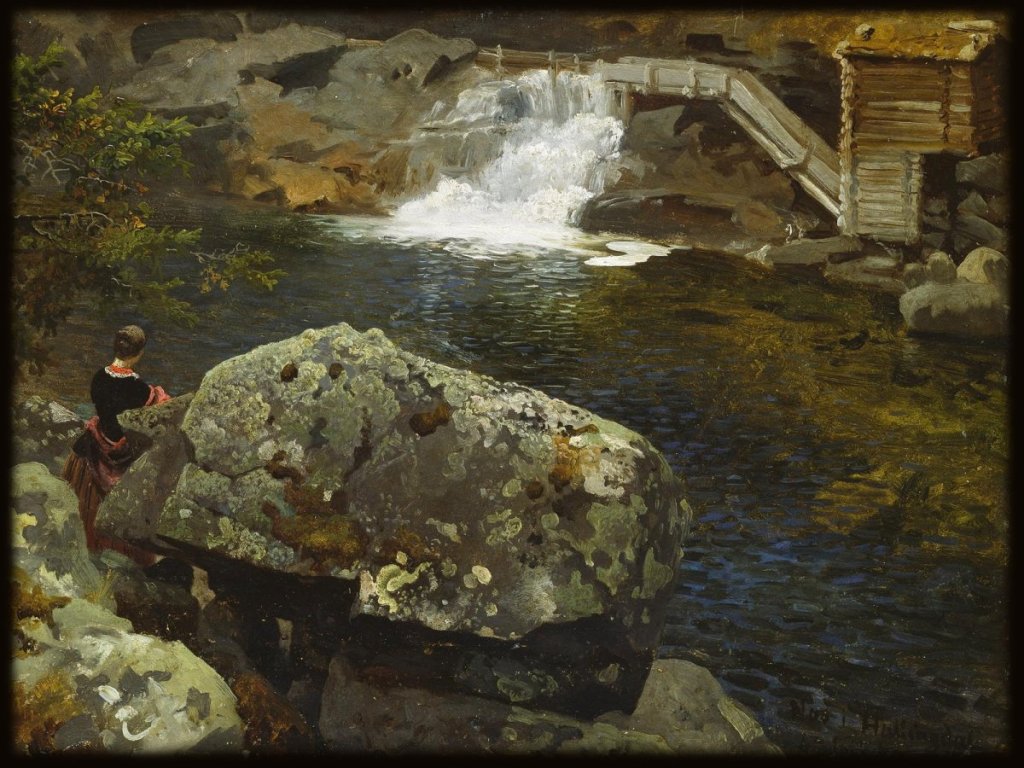

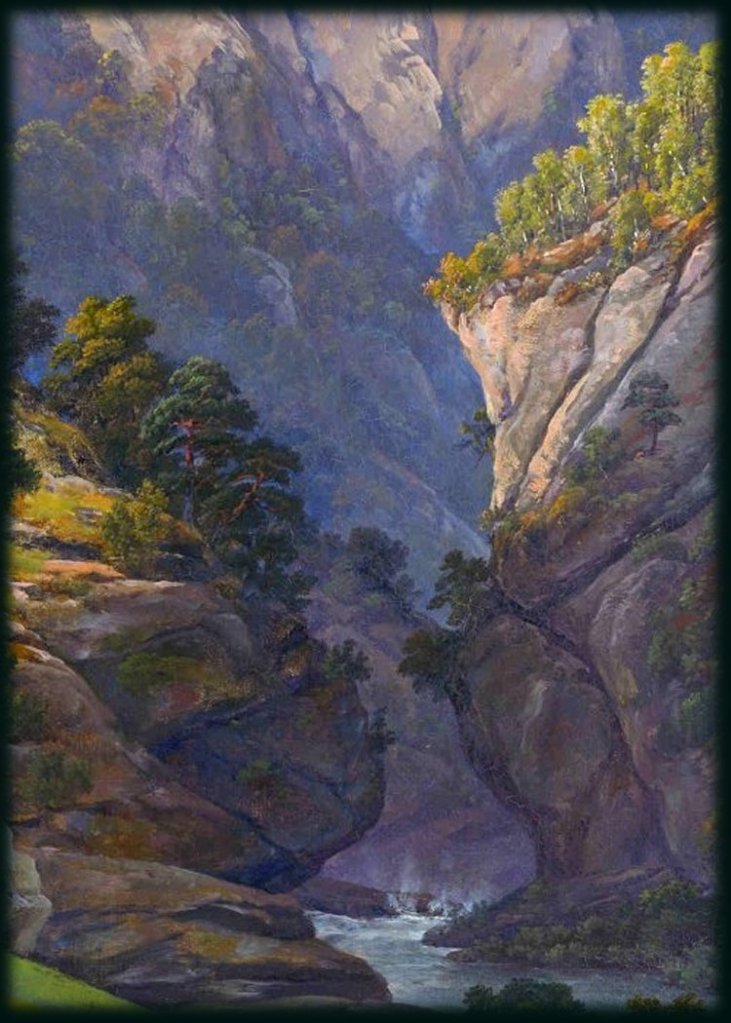

artwork: 19th and early 20th century paintings. Public domain info here.