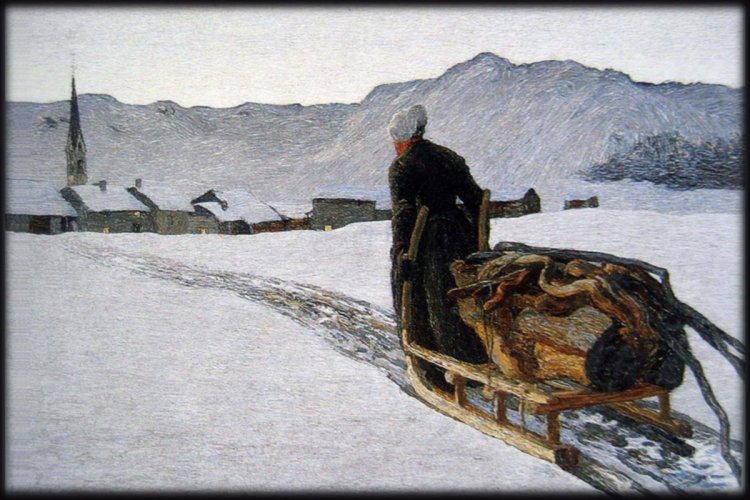

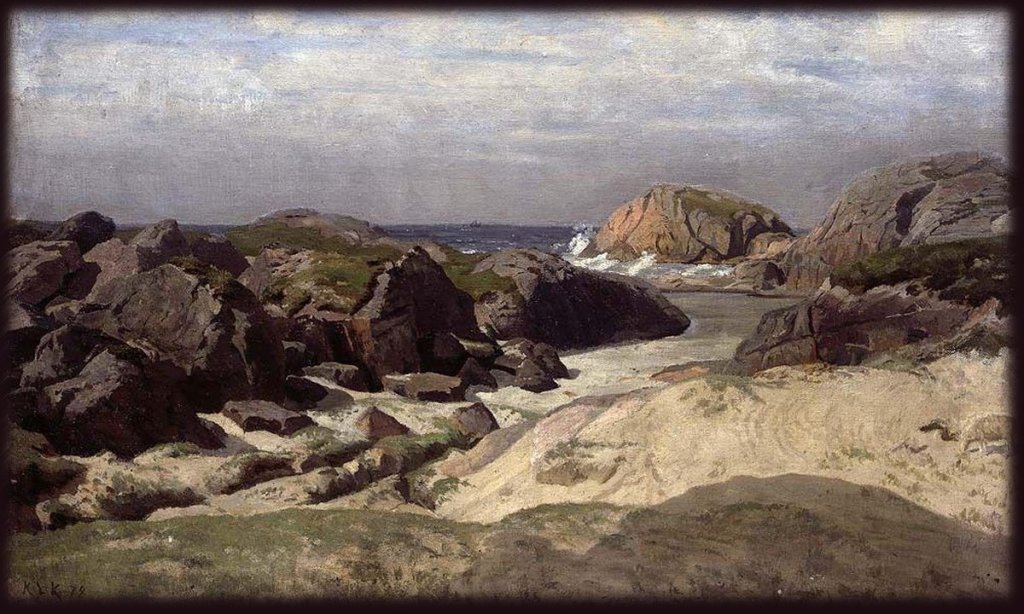

EVENING FELL AS ARNI WALKED DOWN from Mikladalur village to the rocky shore. He found a hiding spot behind an outcropping where he could keep watch on the great flat rocks by the water’s edge.

Winter storms had swept the stage clean just in time for magical Twelfth Night, the last day of the Christmas celebrations. Now gentle waves lapped at the brink of the seal breeding grounds as light faded from the sky.

Arni squinted in the twilight. Seals came swimming from all directions and swarmed up onto the shelving rocks. Just as fable had said, they shed their skins and stepped out, now wearing the shape of everyday people.

He watched in awe. Only on Twelfth Night, legend said, did the seal-folk take human form. He clapped a hand over his mouth to stay silent. One seal-woman, now rising to stand on two legs, radiated such beauty as Arni had never seen before. Lovely as a Valkyrie!

The seal-folk danced and frolicked on the beach under the stars. In the dark, Arni crept toward the spot where that last lovely figure had laid down her sealskin. He took it, and sidled back into hiding.

When dawn’s first glimmer appeared, the seal-folk returned to their skins, slipped into them and waddled back into the water.

The loveliest of all couldn’t find hers. She wrung her hands and wailed as day brightened. Then she spotted Arni, the skin rolled up under his arm. “Give it back, please give it back!” she pleaded.

He stood and walked back up the trail to Mikladalur.

The seal-woman followed. What choice did she have?

Arni married the beautiful woman. He treated her with kindness and love in all ways but one. He kept her seal-skin locked away in a chest. The key always hung from his belt, never out of his grasp.

In time she warmed to him, and forgave him for taking her from the sea. She bore him three children. It was a good life for the little family.

One day while Arni was out fishing with several other men from the village, he was helping haul in a net loaded with fish when his hand brushed his belt. The key wasn’t there.

He cried out in alarm. “This evening I’ll be without a wife!*”

The other fishermen pulled in their lines and rowed home as fast as they could.* When Arni ran in the door of his cottage, he found his three small children huddling on the bed in the cold room, wrapped in quilts. Their mother had put out the fire to keep them safe, and locked up all the knives.

The chest stood open. The seal-skin was gone. And so was she.

Arni moaned and wept. He had cherished her so, and she had grown to love him, too. But with the skin in reach, she couldn’t stop herself from leaving. After all, as the old saying goes, “He couldn’t control himself any more than a seal that finds its skin.*”

As the children grew, they often felt drawn to the rocky beach. Sometimes at dusk, a seal could be seen just offshore watching them.

Arni knew it was their mother.

* dialogue and lines taken straight from the folktale

Nose Bone

ARNI DREAMED OF HIS WIFE, THE SEAL-WOMAN who had fled back to the sea when she found her seal-skin. Oh how he missed her lovely face, her sweet voice. She had loved him truly, and their three children as well.

Years had passed, dulling his grief. So he paid no heed to the warning she brought him in the dream. Just a fond memory, he thought, twisted by the foolish workings of the sleeping mind.

Next morning he joined the other villagers from Mikladalur. They trooped down to the beach with clubs and spears in hand. It was seal-pup season, and the rocky shore teemed with young seals.

Arni and the other villagers clubbed the baby seals to death. An easy harvest in a life otherwise filled with hardship.

He faltered as he approached the cave at the far end of the breeding ground. Just as he’d seen in the dream, a large male seal blocked the entrance, rocking back and forth on his flippers, baring his teeth. “My mate,” his wife had whispered in the night. “Don’t kill him!”

Arni laughed at such folly. He speared the seal, dragged it out of the way. Back inside the cave he found two seal pups, their big eyes staring up in fear. Her sons, she had hissed in the night.

He clubbed them to death.

As his share of the catch, Arni got the whole carcass of the male seal, and the flippers of the pups. For dinner he had boiled seal’s head and flippers. Just as he was sitting down to the table, there came a loud noise and crashing.

The door burst open. In stepped an ugly troll, hideous as scabby driftwood. “You,” she growled at Arni – in the voice of his seal-woman wife. “You!” she howled. “What have you done?”

She sniffed in the serving bowls, then roared like storm waves crashing upon the rocks. “Here is the nose bone of the old man, and here, Haredur’s hands and Fridrikur’s foot! Avenged it is and avenged it will be on the men of Mikladalur! Some will be lost at sea, and some will fall from mountain cliffs and ledges! And this will go on until so many have died that they can hold hands and reach all the way around Kalsoy!” *

With a great crashing, she disappeared, never to return in life or by dream. And her curse came true. Men of Mikladalur often perish at sea or fall from cliffs.

There is still a foolish farmer on the south-most farm, where Arni once dwelt, so it must be that the number of men that have fallen to the seal-wife’s curse is not yet enough to reach around the island.

* the wife’s whole rant taken straight from the folktale

text of Twelfth Night and Nose Bone: © 2022 Joyce Holt

artwork: 19th century century paintings. Public domain info here.