SIF STRODE OUT TO THE COURTYARD. Ash trees leaned over the wall, leaves quivering in the breeze and casting speckled shadows across banquet table and gilded chairs. “Bryn,” Sif called. “Have you seen my husband?”

A dark-haired young woman looked up from the dagger she was whetting. “No. What has he done this time?”

Sif tossed her golden tresses. “Do I look upset? Just curious. See what I found in the household treasure chest!”

Sif set out a board and markers

“A hnefatafl game,” Bryn said, sheathing her dagger. “Made of gold! Has he been dealing with the dwarves again?”

“I don’t know. None of my jewels are missing, so he must have won this some other way. Play a round?”

The two women tossed a golden die to see who would field a king and defenders, and who would man the attacking army. Bryn’s thin lips sharpened into a predatory smile. She gathered up her game pieces. “I have yet to lose when I invade.”

Sif bristled. “I have yet to lose when I defend. Feel like wagering on the outcome of our game?”

After much dickering the two agreed on their stakes. A magnificent ruby on Sif’s part, and on Bryn’s, the pick of the loot from her next foray to Midgard.

The golden die rolled on the banquet table’s inlay, chiming like a bell. The players placed their pieces, one by one. Bryn made her moves with swift sure steps, her attackers clicking like talons on bone. Sif took longer on her turns, sliding the defenders with the softest of whisks.

Sif lost ground, then regained it. Bryn cursed, and songbirds scattered.

Footsteps tromped about inside the hall, and a voice thundered, “By Odin, what thief dares break into my chest?”

“Out here, husband dear,” Sif called. “No one’s stolen anything. I found it and came looking for you, but thought I’d give it a–“

“Fool woman, put that down!”

Sif scowled at the hulking redbeard in the doorway. “It can wait a moment. I’m just two steps from winning–“

“No, you’re not.” The Valkyrie Brynhildr rose with an invader piece in hand. “Because I’m just one step from–“

Thor whirled his hammer, though he did not release.

Brynhildr staggered back, and the game piece went flying.

“Put,” Thor shouted, “those–pieces–down!” With each word-blast he stomped a great stride across the courtyard.

Both women meekly obeyed.

“Now gather them back to the starting positions,” he ordered.

High above Asgard an eagle screamed. Two ravens circled Odin’s watchtower. A squirrel nattered in the ash branches.

Thor listened to the tidings, then turned to his wife. “This board came from the Norns, the spinners of fate. Your idle game here set in motion a war in the world of mankind. We nearly lost our greatest flock of adherents! But truce has been called, in the nick of time.”

Sif sniffed. “Men and their toys!”

Loosely based on Norse mythology. The Old Norse played hnefltafl, a distant cousin of chess. Attackers and defenders had different numbers of playing pieces, and the board was marked with areas of refuge or blockade.

text: © 2022 Joyce Holt

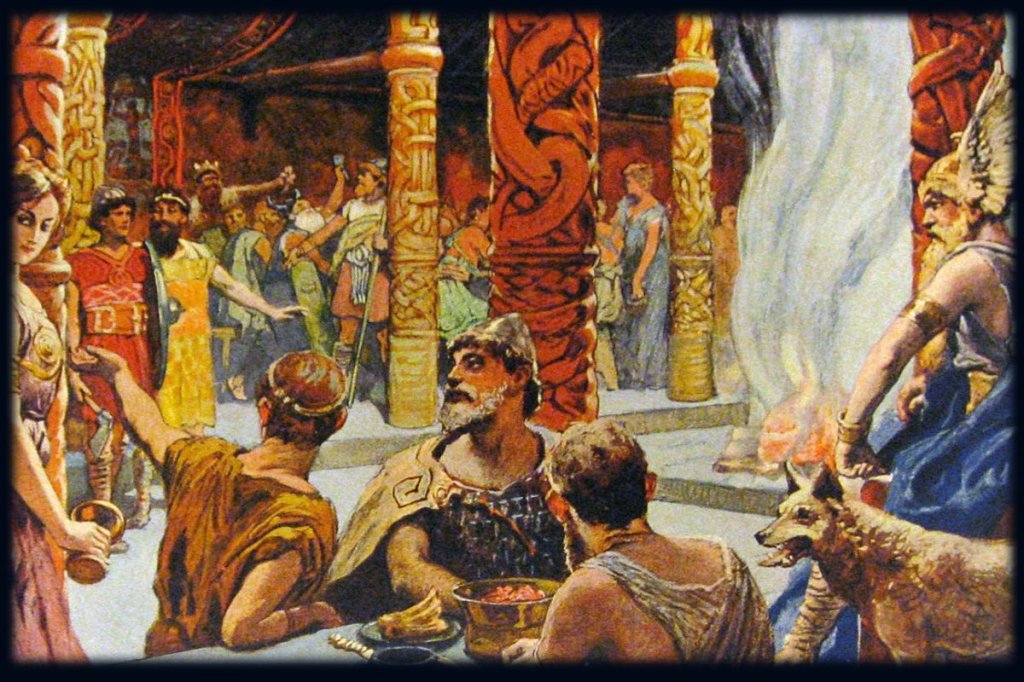

artwork: early 20th century century painting. Public domain info here.