THE BUNDLE IN HER LAP STIRRED. A small hand tugged a flap of blanket aside and a pair of eyes blinked at the early morning light. “Mama!”

Maryam smiled. “Good morning, sweetie.”

A finger pointed. “Sky!”

“Yes, we’re out and about already. Going for a ride.”

“Bed?”

“Bye-bye to the bed.”

“Papa?” The child arched to look around. “Bye-bye Papa?”

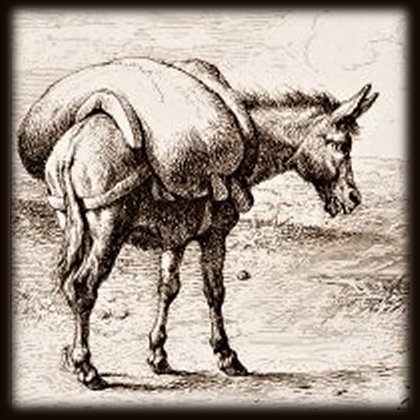

“No, Papa is right here, leading the donkey.”

“Clop clop clop!”

“Yes, cloppity clop.”

“Oh oh. Papa, oh oh!” The child squirmed.

Her husband shot her a glance.

She nodded. “We need a stop.”

Yossef shielded his eyes, gazing back along their path. “A quick one should be safe,” he muttered. He took the child from her arms and to the side of the trail.

Maryam rummaged in a saddlebag. “Hungry, sweetie?” she asked when they were done. “Here, a hunk of bread and some dried figs.”

“Yum!” The child nestled back in her lap and nibbled his breakfast.

Maryam and Yossef both cast glances to the north, then took up their rapid pace again.

“Walk! Me, walk, Papa, now.”

“No, we need to go fast. Clippety clippety clop!” She tickled the child.

He giggled, then gazed at the rocky scenery passing by. “Go Yoyo?”

“No. Yohanan isn’t home.”

“Yoyo go ride?”

“Yes. Yohanan is riding that way.” Maryam pointed east. “We’re riding this way.” She pointed south.

The child gazed eastward in silence a while. “Yoyo catch hoppers.”

Maryam laughed. “Yes, he loves to catch grasshoppers.”

He pointed east. “Yoyo safe.”

“Yes. And Auntie Liz is safe, too.” Maryam dropped her voice. “Pray God they’re safe.”

The child looked up with earnest gaze. “Papa safe. Mama safe.” He clapped. “Walk now?”

“We’ll slow down and walk when Papa says we can.”

Yossef glanced back. “When did he pick up ‘safe’?”

“Just this morning. According to him, we’re now out of danger.”

Yossef met her gaze for a thoughtful moment. “Well, we’re not slowing until we catch up with the caravan. Which shouldn’t be much longer, by the way that pile of camel dung is steaming.”

“Dung, dung, dung,” the child chanted, trying out another new word.

“I see a bird!” Maryam chirped. She pointed out a lark flitting through the chill morning air. “I bet it’s looking for hoppers, just like Yohanan.” She told him stories, and played finger games, and sang her favorite psalms. “Look!” she said at last. “See the camels?”

“Little!”

“When we get close, you’ll see how big they are.”

A caravan guard came riding back to check for threats. Yossef asked to join the procession, and negotiated a price for protection — one of the gold coins they’d been gifted a couple weeks before.

The guard galloped back to his fellows on the high horizon.

When the donkey finally crested that same spot, the land beyond spread out before the travelers.

“See the long-legged camels?” Maryam said. The caravan wasn’t far off now. “See what big loads they carry, so much more than a donkey can.”

The child gazed silently at the vista beyond the caravan. He pointed at last into the hazy southeast. “Egypt,” he said, the word ringing clear.

Maryam and Yossef looked at each other. Had little Yeshua heard their frantic whispers in the middle of the night? “Yes,” she said. “We are fleeing to Egypt.”

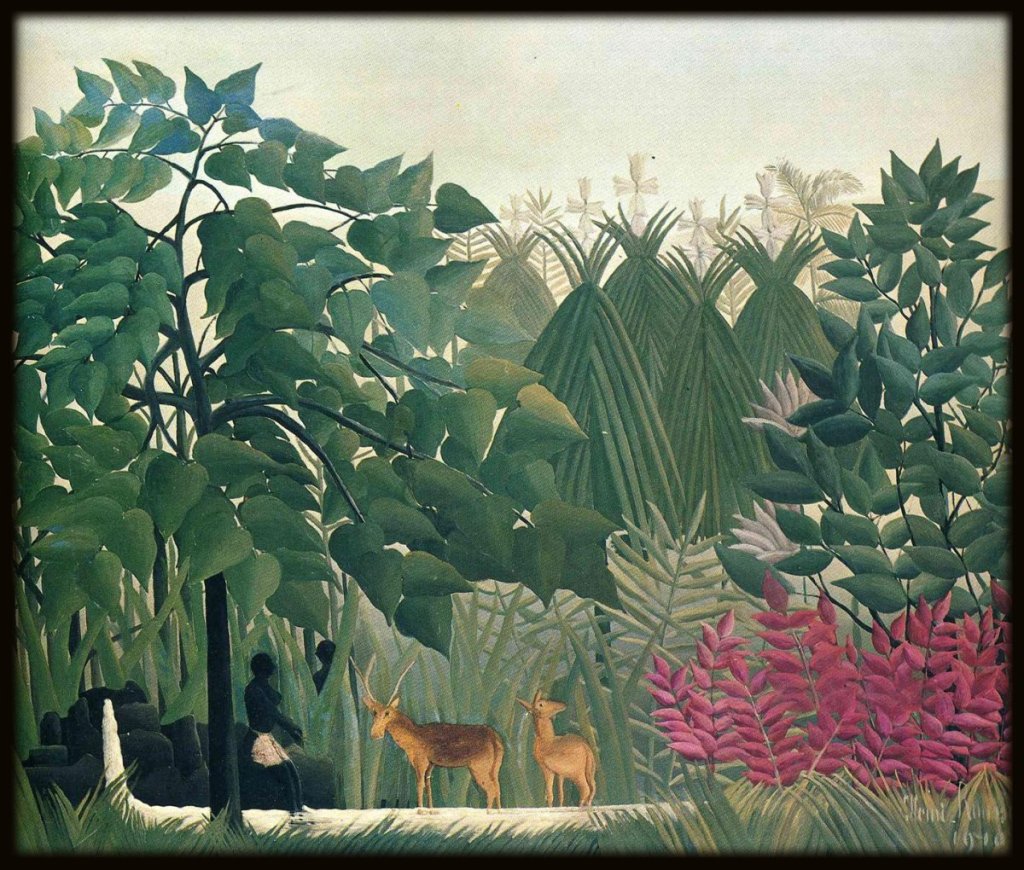

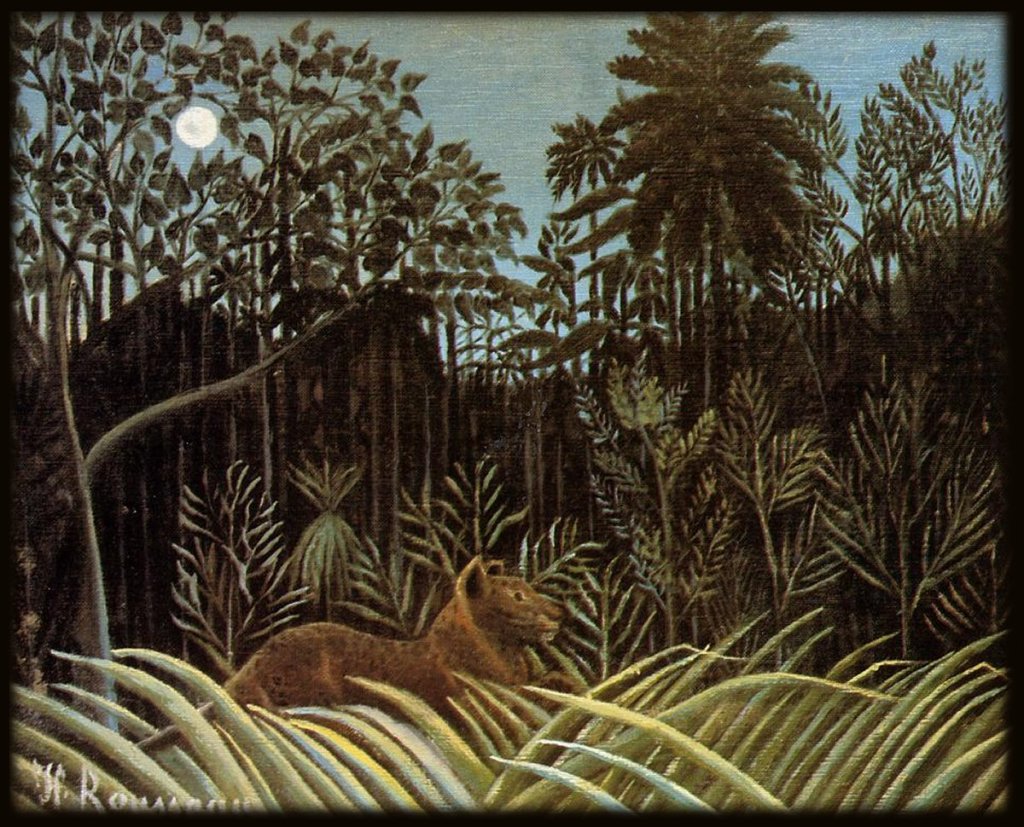

The Christ Child was probably near the age of two at this time.

Names: in Aramaic (the Semitic language spoken by Jews in the Near East from about 6th century BC to 7th century AD)

The Hebrew and Aramaic word for Egypt was Misrayim (among other spelling variations).

text: © 2023 Joyce Holt

artwork: 17th and 19th century paintings. Public domain info here.